Artificially Inequitable? AI and closing the gender gap

New AI models have taken the world by storm, but policy makers should focus on the basics to ensure AI plays a positive role in closing the gender gap

In what became the first celebration of International Women’s Day in 1911, more than a century ago, women worldwide gathered to fight for their right to education, work, vote, hold public office, and end discrimination. That same year, the first Model-T car rolled off the assembly line, and the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company was founded, later renamed IBM. Decades later, British mathematician Alan Turing would first question whether machines can think, and the term artificial intelligence (AI) was coined in 1956.

Women’s rights, their economic empowerment, and technology have advanced considerably in the last century. Advances in machine learning, large datasets, and increased computing power have driven AI development in recent years, moving from academic discussions into remarkable real-world applications with real opportunities and challenges for gender equality.

For many, 2022 was the year AI became real. The rise of foundation or general-purpose AI models, including the emergence of very large language models, paved the way for a “generative AI” renaissance, with AI that generates novel content, transposes text-to-video and -image, and offers advanced chatbots accessible to all. AI tools became mainstream with the release of AI model ChatGPT, which reached about 100 million monthly active users in just two months, making it the fastest-growing consumer application in history.

With AI tools already changing work, education, and leisure in significant ways, we must ask: is today’s AI addressing the gender equality issues that have plagued policy makers for decades? While women have gained the right to education, work, vote, hold public office and protection against gender discrimination, technologies play a big part in ensuring those rights are upheld. Are policy makers doing enough to ensure that today’s AI systems do not perpetuate yesterday’s biases?

Same but different: will AI help close the gender gap?

Although technologies have evolved, some barriers to gender equality and economic empowerment are still much like the ones women faced over a century ago when the world celebrated the first International Women’s Day. In many countries, women still have less access to training, skills, and infrastructure for digital technologies. They are still underrepresented in AI research and development (R&D), while harmful stereotypes and biases embedded in algorithms continue to prompt gender discrimination and limit women’s economic potential.

Today, men are leading most cutting-edge AI companies, while female voices animate most Virtual Personal Assistants (VPAs) and advanced humanoid robots – like Alexa and Siri, or robots Sophia, Ameca, Jia Jia, and Nadine. This reflects gender biases at home and in the workplace by reinforcing traditional norms of women as nurturers in supporting roles.

New generative AI tools can also produce overtly sexualised digital avatars or images of women while portraying men as more professional and career-oriented. As generative AI and robotics advance, their effects on women’s economic and social equality remain to be seen.

Generative AI tools need appropriate guardrails to avoid gendered mis- and disinformation

Generative AI tools bring exciting opportunities to increase productivity. But AI-generated content can also produce fake news, deep fakes, and other manipulated content so convincing that it is impossible to tell them apart from real ones. Without appropriate guardrails for the use of such tools, their increasing prominence can exacerbate certain risks like mis- and disinformation.

Women, particularly those in politics and other leadership positions, are increasingly targets of gendered mis- and disinformation campaigns. This phenomenon tends to be even more pronounced for female political leaders from minority groups who are highly visible in the media and vocal about feminist issues. These risks have a silencing effect on women, about half of the world’s population, pressuring them to disengage online and avoid politics and other male-dominated careers where they are more at risk of being targeted.

Women still lag in digital skills, but trends in AI talent look promising

As AI transforms labour markets, demand for digital and AI-specific skills increases. But women still lag behind men in digital and AI skills development. In OECD countries, more than twice as many young men than women aged 16-24 can programme, an essential skill for AI development. In 2019, women represented only 18% of C-suite leaders in AI companies and top start-ups worldwide. This limits women’s economic potential as employers increasingly look to hire professionals in AI and science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).

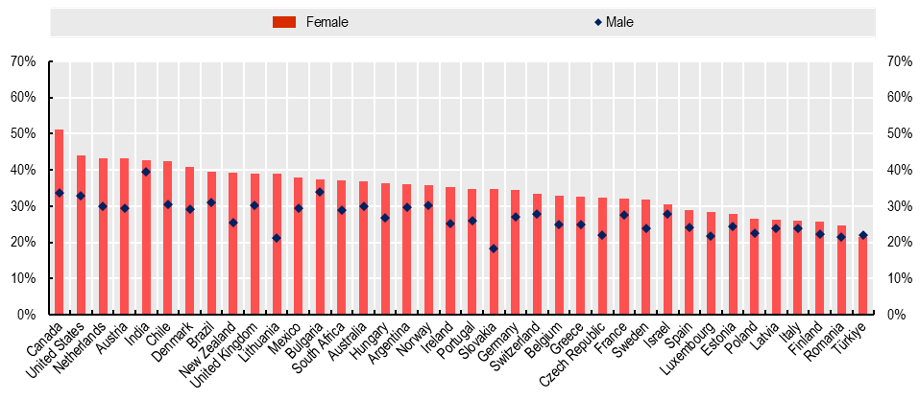

At this point, it should be no surprise that female professionals with AI skills represent just a small proportion of workers. For example, men are twice as likely to report AI-related skills on LinkedIn than women. However, promisingly, female AI talent is growing faster than male AI talent (Figure 1).

Figure 1. AI talent concentration by country and gender, average annual growth rate, 2020-2022

Source: adapted from OECD.AI, using LinkedIn economic data.

More and more women in AI R&D but far from parity

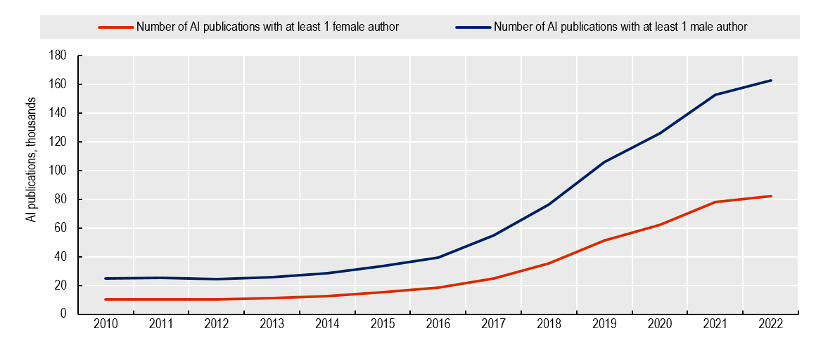

To reap the full benefits of diversity, women must lead and participate in AI R&D. AI research is still primarily dominated by men: in 2022, only one in four researchers publishing on AI worldwide was a woman. While the number of publications co-authored by at least one woman is increasing, women only contribute to about half of all AI publications compared to men, and the gap widens as the number of publications increases (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Number of AI publications by gender globally, 2010- 2022

Source: OECD.AI (2023), visualisations powered by JSI using data from Elsevier (Scopus).

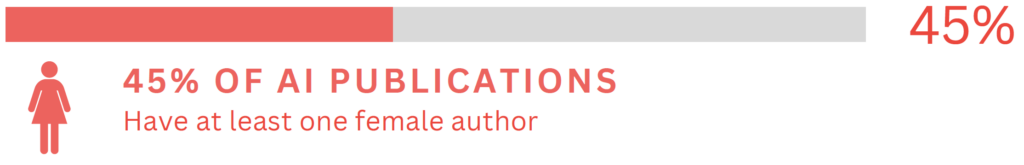

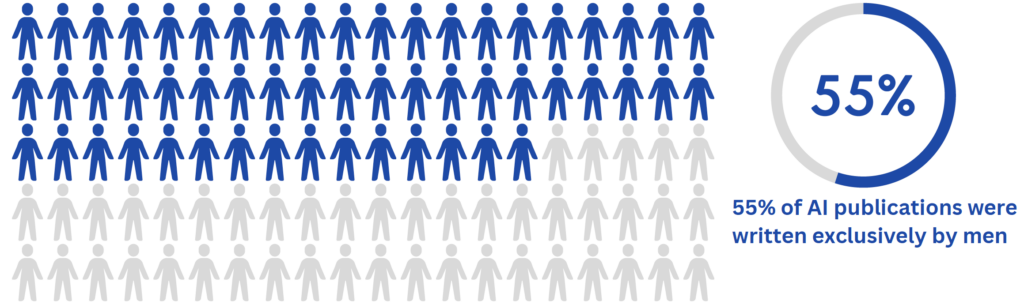

Women contribute to roughly 45% of AI publications worldwide, compared to almost 90% that list at least one man as a co-author. More strikingly, only 11% of AI publications are authored solely by women, while 55% are penned by men alone.

Figure 3. AI publications by gender globally, 2022

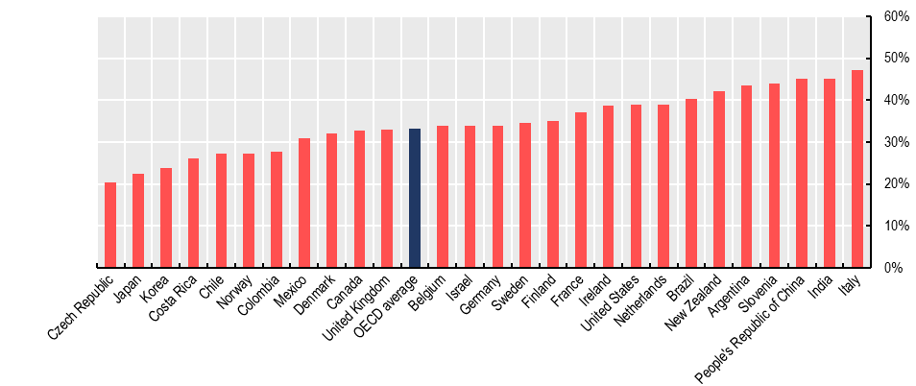

The data reveal significant disparity across countries: Italy tops the ranking with 47% of AI publications authored by at least one woman, closely followed by India and China, whereas in the Czech Republic, Japan and Korea, only about one in five AI publications is authored by at least one woman (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Share of AI publications with at least one female author, select countries, 2022

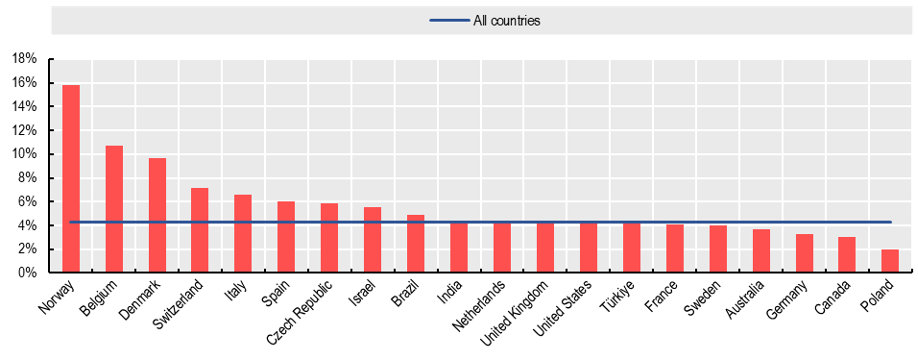

Female developers in AI are an even smaller minority than researchers. A 2022 survey of Stack Overflow users – a popular platform for knowledge sharing among developers and computer programmers – shows that slightly over 4% of respondents are female. But countries like Norway, Belgium, Denmark, Switzerland and Italy stand out for having a higher, but modest, share of female AI developers (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The proportion of female data scientists or machine learning experts participating in the Stack Overflow survey, by country, 2022

Source: Adapted from OECD.AI, using data from Stack Overflow survey.

Policy makers should focus on the basics to make sure AI helps close the gender gap

Policies and programmes that support digital and AI-specific skills development for women will help them succeed in tomorrow’s labour markets. These skills will also help workers understand how AI systems are being implemented and to raise concerns when necessary. Governments are already proposing and implementing thoughtful policies to address AI skill development for women across OECD countries. Here are a few examples.

As part of the Pan-Canadian AI Strategy, the AI For Good Summer Lab (AI4Good Lab) programme provides women in STEM fields with AI training and networking opportunities. Alumni from the lab have already founded AI start-ups and are developing machine learning tools that use natural language processing to detect gender biases in text.

In the United States, the Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning Consortium to Advance Health Equity and Researcher Diversity (AIM-AHEAD) Program establishes partnerships to increase the participation and representation of researchers from underrepresented communities in AI and machine learning. The programme aims to make electronic health record data more representative so that training data is of higher quality. Ultimately, this should diminish health disparities and inequities. It also addresses algorithmic bias by ensuring data from different genders, ethnicities, and backgrounds are accounted for.

In the Netherlands, the Ministry of the Interior and researchers studied the technical, legal, and organisational considerations for organisations using AI in their operations. This resulted in a step-by-step guide for government organisations and companies to prevent discrimination. The guidelines stress the importance of involving stakeholders early on, starting with algorithm development. People affected by automated decisions must be informed and given the means to object to them when necessary.

While AI is a powerful tool for women’s economic empowerment, it can be a double-edged sword if representation, bias, and discrimination issues are not adequately addressed. Policy makers should go back to basics when it comes to making sure AI helps close the gender gap by focusing on digital skills, supporting women in AI R&D, AI commercialisation and ensuring harmful gender stereotypes and biases are kept in check. With a thoughtful policy approach, AI developers, policy makers, and users can create an inclusive and empowering environment for all women and diverse groups to thrive in an AI age.

The authors thank Besher Massri and Jacqueline Lessoff for their input and contributions to providing data and visualisations informing this blog post.