AI in Government: Issues > Overview

Governments are one of the most important adopters of artificial intelligence (AI) and yet, they are also one of the most cautious. This tension isn’t merely organisational inertia—it reflects governments’ unique responsibility to their citizens. Governments’ use of AI can boost public sector productivity, responsiveness and accountability — but can also pose risks such as […]

Governments are one of the most important adopters of artificial intelligence (AI) and yet, they are also one of the most cautious. This tension isn’t merely organisational inertia—it reflects governments’ unique responsibility to their citizens. Governments’ use of AI can boost public sector productivity, responsiveness and accountability — but can also pose risks such as data protection and surveillance concerns and the potential for skewed outcomes. Inaction may mean missed opportunities, while challenges such as insufficient guidance or data slow progress.

The state of play of AI in government

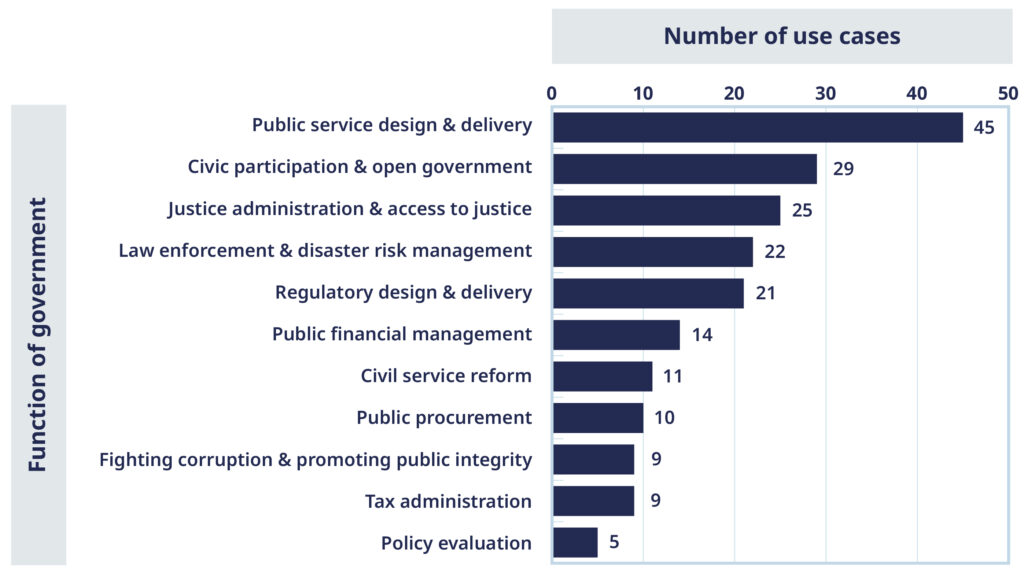

AI is becoming a significant component of digital government. The OECD conducts in-depth analysis on the use of AI in a variety of government functions, as outlined on the sub-tabs on this page. The analysis of 200 use cases, shows that AI adoption is most prevalent in public service, justice functions and civic participation, followed by public procurement, financial management, fighting corruption and promoting public integrity, and regulatory design and delivery. Relatively less use is seen in policy evaluation, tax administration and civil service reform

There are a variety of explanations for this distribution. For instance, some functions encompass a wider variety of uses (public services) while others are more narrow (civil service reform, tax administration). Also, some face more regulatory constraints (e.g. tax administration, given rules on using tax data), while some face fewer implementation challenges and can mature faster (civic participation). In some functions (such as justice administration) public demands and growing transaction backlogs may precipitate AI adoption as an opportunity to tackle urgent challenges.

OECD work continues to explore the use of AI across government functions to better understand the factors that support or hinder AI adoption to promote trustworthy AI in government aligned with the OECD AI Principles.

Breakdown of 200 OECD-analysed use cases across government functions. Use cases across the European Union (EU) and Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) follow similar trends.

AI poses tremendous potential benefits

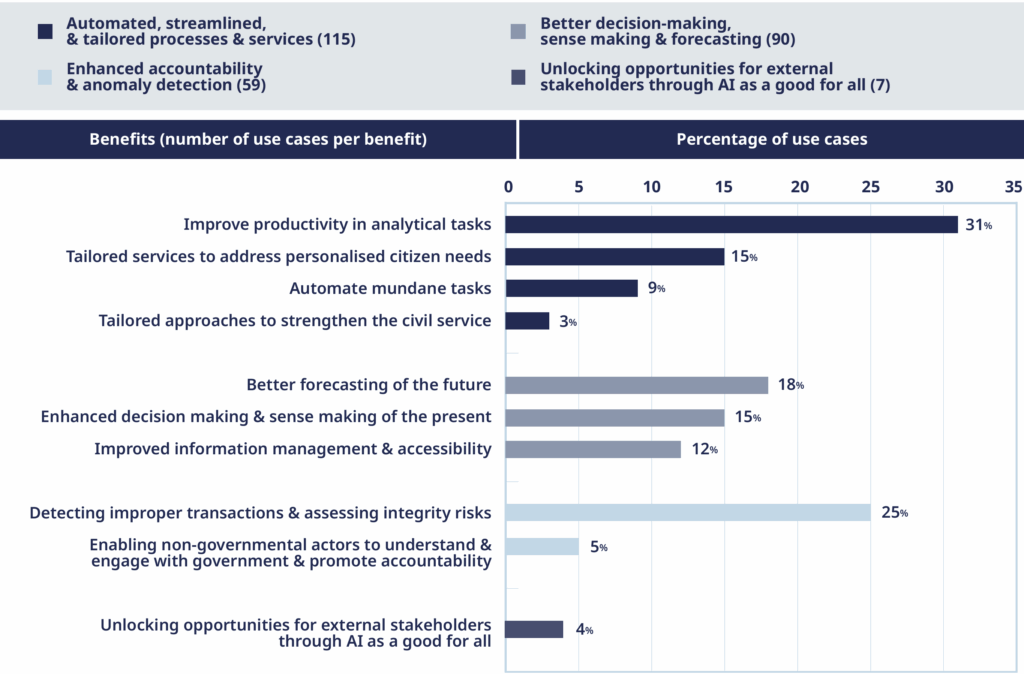

OECD analysis of 200 government AI use cases and the benefits they seek to obtain.

AI offers governments a wide range of benefits across public operations, decision making and service delivery. When developed and used in a trustworthy manner, AI can help make governments more efficient, effective and responsive to the needs of the people they serve.

Below are key areas where AI is making a difference:

- Automated, streamlined and tailored processes and services. AI helps automate and augment routine tasks and analytical work, improving efficiency and quality; it enables personalised services and promotes better hiring, training and knowledge sharing in the civil service.

- Better decision-making, sense-making and forecasting. AI provides data-driven insights across the policy cycle, detecting issues, analysing large datasets and reducing errors for faster, more consistent decisions in forecasting, risk management and regulation.

- Enhanced accountability and anomaly detection. AI can help uncover fraud, flag anomalies and assess integrity risks, strengthening oversight in tax, procurement and regulatory compliance; it also supports transparency and civic oversight.

- Unlocking opportunities for external stakeholders through AI as a good for all. By opening AI tools, infrastructure and data to non-governmental actors, governments can spur innovation, foster economic development, meet underserved needs and share benefits widely.

AI also poses significant risks

Using AI in government presents risks alongside its potential benefits. Governments have a responsibility to ensure these technologies are used safely, fairly and transparently. The risks are outlined below:

- Ethical risks. Poor-quality or skewed data can drive adverse outcomes; surveillance, privacy infringements and data misuse threaten the free exercise of rights. If not developed and used in a trustworthy manner, the use of AI can erode trust, autonomy and accountability.

- Operational risks. Hallucinations, failures and automation bias (i.e. over-reliance on AI) can cause errors at scale. Opaqueness and cybersecurity threats can undermine effectiveness and public trust.

- Exclusion risks. AI can exclude digitally underserved groups. Personalisation and other benefits of AI may favour data-rich users; public-sector roles risk displacement if there is not adequate re-skilling.

- Public resistance risks. Limited understanding, past misuse and opaque decisions can fuel scepticism and distrust; without transparency and engagement, there can be public backlash to government use of AI.

- Risks of inaction. Over-focusing on harms can deters safe, high-benefit uses, resulting in missed opportunities. Inaction can also contribute to a widening gap between public sector and private sector capabilities.

Understanding and managing these risks is essential for building trustworthy, inclusive and effective public sector AI.

Governments face a variety of challenges in adopting AI

Applying AI in government presents a variety of challenges that can slow or prevent the transition from experimentation to impact. These challenges are often interconnected and require coordinated responses across policy, technical and organisational dimensions. Governments must navigate the following implementation challenges:

- Challenges in moving from experimentation to implementation. Many initiatives remain in pilots; without clear scaling pathways, structured learning, quality data, documentation and defined ownership, successful trials are not often scaled or replicated.

- Skills gaps. Limited internal expertise slows progress, increases reliance on vendors and constrains the capacity to design, operate and evaluate AI; recruitment and retention remain challenging.

- Lack of high-quality data and the ability to share it. Data quality issues, inconsistent formats and legal or institutional barriers—combined with weak governance and interoperability—impede training, deployment and scaling.

- Lack of actionable frameworks and guidance on AI usage. Strategies exist but practical guidance is thin; unclear rules and examples create uncertainty, slowing adoption and producing uneven practice.

- Driving innovation while mitigating risks. Risk aversion and concern about scrutiny constrain experimentation; proportionate arrangements for safe testing and iterative learning are needed.

- Demonstrating results and return on investment. AI benefits are hard to evidence; few projects undergo rigorous evaluation or comparison with alternatives, weakening the case for scaling.

- Inflexible or outdated legal and regulatory environments. Frameworks often lag technology; legal uncertainty or strict, outdated rules can delay adoption and complicate compliance.

- High or uncertain costs of AI adoption and scaling. Licensing, cloud, staffing and procurement can generate substantial and uncertain costs, with few benchmarks or funding models to support sustained investment.

- Outdated legacy information technology systems. Legacy systems are often incompatible with modern AI, limiting data use, increasing security risks and diverting budgets from innovation.

Addressing these challenges requires not only technical fixes but also shifts in governance, procurement, and culture. Strategic investment, capacity-building and a willingness to learn from both successes and failures are essential for unlocking AI’s full public value.

OECD Framework for Trustworthy AI in Government

The OECD Framework for Trustworthy AI in Government serves to guide governments unlock AI’s potential while mitigating risks and overcoming implementation challenges. The framework is organised around three pillars:

- Enablers to facilitate adoption, such as governance approaches, data, digital public infrastructure, skills, financial investments, agile procurement processes, and capacities to partner with non-governmental actors.

- Guardrails to guide the trustworthy use of AI, such as policies, guidance and frameworks, transparency and accountability mechanisms, and oversight and advisory bodies to guide and evaluate efforts.

- Engagement approaches to shape user-centred and responsive approaches, including mechanisms to engage with key stakeholders, including the public, civil society and businesses.