Unpacking the ‘AI wardrobe’: How national policies are shaping the future of AI

Grand pronouncements about artificial intelligence appear daily: AI will produce autocrats and demolish democracies. Algorithms are replacing workers and do not lead to prosperity. Data flows remain an alarming cause for concern from governments to human rights activists. There are also optimistic declarations that say AI is the fourth industrial revolution and positively transforms our politics, economics and society.

Academic research can provide empirically grounded answers to the above declarations in the sea of high-level insights about AI’s impact. My colleagues and I are doing significant work whose findings are evidence-driven. They confirm some of these declarations while providing sobering counterpoints to others.

The large interdisciplinary team of AI researchers at George Mason University that I lead uses AI to examine AI-related policies and regulations from governments worldwide as they evolve. We find regional variations in AI governance and break them down into pluralistic or autocratic systems, advanced states and those in the developing world. Increasingly, we see more detailed approaches to some of the biggest issues in AI today: the economy, workforce development, contracts and liability, data flows, transportation, and health.

More specifically, we are interested in how the values and priorities embedded in global AI policies and regulations evolve worldwide. Our team includes political economy, security, and ethics analysts from the social sciences and machine learning and natural language processing experts from the computer sciences. We are very grateful for the project’s funding, which comes from a $1.4 million competitive research grant from the Minerva Research Program at the U.S. Department of Defense.

The first phase of our project focuses on national AI policies from over seventy countries found in the OECD’s AI policy repository, developed primarily as a tool for policymakers and researchers. Here are some highlights from our forthcoming report in International Studies Quarterly and those published in a global infrastructures report:

The AI wardrobe, where the same pieces produce many results

We coined the phrase ‘AI Wardrobe’ in 2022 to connote the variable mix of common elements for understanding national AI policy infrastructures. Individual national AI policies combine similar items, but the wardrobe looks different in each context.

The AI wardrobe consists of macro issues such as types of research capabilities, workforce development, data regulation policies, and international collaboration. Leaders like the United States, EU, China, Japan, and Korea showcase high basic research capabilities, whereas developing countries might adopt approaches encouraging tech hubs.

We also find cross-cutting issues in the macro ones, including priorities for start-ups, encouraging unicorns, and mixes of agriculture, manufacturing, and services capabilities. Advanced countries widely deploy crop sensors and computer vision technologies to monitor crop patterns. In contrast, the developing world is just starting to use them to detect early outbreaks of diseases on crops.

Image designed with AI by Caroline Wesson and Manpriya Dua

Familiar clusters and regions come together around similar AI policies

Our analysis of the large ‘corpora’ of national-level AI policies reveals the overall direction a country might take toward AI and often how they posture toward each other, for example, in the way the United States and China declare themselves to be front runners in an AI race.

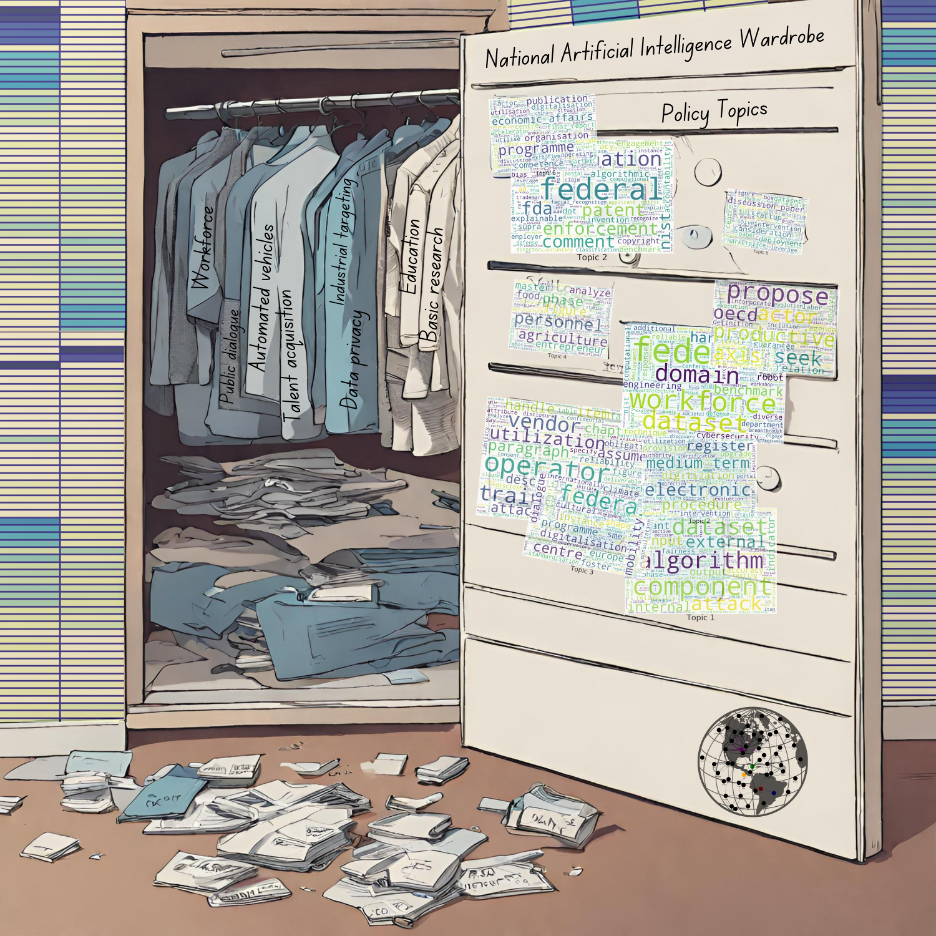

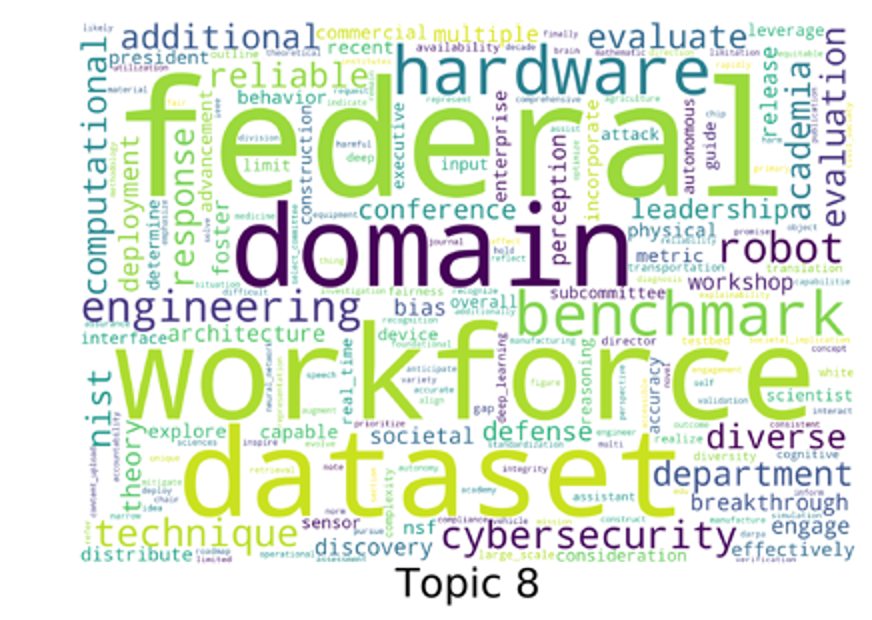

We employed Latent Drichelet Allocation machine-learning techniques to analyse topics in AI policies. LDA approaches locate topics discerned from the probability of words occurring together in a text. Figure 1 provides the word cloud from the most important topic found in the European Union AI Strategy, which focuses a great deal on the programmatic and organisational aspects of the EU’s AI policies while outlining goals in specific areas (labour, well-being, enterprise, patient, societal, human-centre, etc.).

Image from LDA analysis executed by Amarda Shehu and Manpriya Dua

We employed the ensemble-LDA or e-LDA techniques to pool results from large LDA iterations to stabilise our results. In jurisdictions like the United States, China, Germany, Japan, and South Korea, we find distinct topics emphasising basic science capabilities. In pluralistic states such as the United States, Germany, Japan, and South Korea, the emphasis on science is accompanied by processes such as dialogues and consultations with societal groups and stakeholders in policymaking. However, in China, AI policy mostly addresses science, economic and security advantages, and workforce talent.

We also identified regional clusters with our eLDA algorithms that make intuitive sense: an Ibero-American Cluster, an EU cluster, an East Asian states cluster, and a Commonwealth and English-speaking cluster. These clusters have varying levels of economic development, societal inclusion, and data regulation priorities. But there are ‘post-colonial-link’ surprises. Spain and Portugal cluster with Latin America and contain topics that intersect with the EU. Another post-colonial link is found in the UK and Commonwealth influence cluster. We hypothesize that states learn from each other, and colonial and linguistic ties still matter in this situation. For example, the Spanish national plan’s emphasis on broad objectives (ejes in Spanish) gets picked up in some Latin American plans. While presenting in 2023 at the Foro Globo focused on AI, we noticed several Spanish officials and representatives from several Caribbean and Latin American states at the conference. This implies that networked learning may contribute to clustering in plans.

Countries with advanced AI capabilities focus on more topics

National plans often lay out broad, declaratory visions that signal things to other states or domestic constituencies that may or may not be achievable. Therefore, along with national plans, we examined policies and reports from national ministries, departments, commissions, and regulatory agencies such as data protection directorates and technology standards organisations. Having more plans from each country brings out policy depths and consistencies.

The results are not what we expected, but they make sense. We thought we would find documents covering a wider range of topics. Instead, we found that nearly three-fourths of all countries focus on three topics: basic infrastructural provision (digitization, sandboxes, workforce development, societal and labour issues), regulation, and contracts.

Countries leading the AI race have more distinct advanced-level topics, greater differentiation in regulatory agencies and design, and greater science capabilities. These countries are the United States, China, Germany, Japan, and South Korea, which are notable for their high basic science and innovation capacities. The European Union stands out for its regulatory policies.

Priority topics among advanced governments

We also ran the eLDA algorithm on all the documents without considering national plans to see which topics are important across governments. Our sample included 38 countries, all with departmental or organisational plans that go beyond national AI strategies.

The eLDA algorithms yielded five topics. The table below presents these topics and the number of countries with relevant documents.

| Topic | Number of countries |

| Data and governance | 30 |

| Education and training | 30 |

| Economy | 36 |

| Contracts and liability | 35 |

| Transportation | 33 |

The Hellinger distance in eLDA modelling provides the correlations among topics. The topics of economy and education are highly correlated. Similarly, the topics of data, regulations, contracts, and liabilities correlate. These correlations guide future policymakers on organising priorities for their economic and regulatory systems.

As an example, we found that Chinese documents dominate the education and workforce development topics.

We also found that a distinct transport topic stands out, whereas there are not many documents on the health topic. This suggests that health AI plans in various national contexts are not as highly developed as the media hype might suggest. It could also be that the data governance topic includes many top-level health and AI concerns.

Innovation is present across varied country profiles and governing approaches

Countries present national strategies that are often supplemented with ‘subnational’ documents from ministries, departments, and commissions that deal with specific sectors or regulatory issues. At the national level, strategies include innovation in various ways, and here, we provide three instances.

First, more advanced countries emphasized basic science and high levels of innovation in algorithms and applications. Contrary to popular wisdom that correlates innovation with democracies, we find that pluralistic countries such as the United States and autocracies such as China both feature high levels of innovation. At the same time, the innovation focus is somewhat muted in the EU strategy. There are many references to science, engineering, and technology capabilities in the topic for the United States, China, and Japan at the national level in the figure below compared to the mostly policy and regulatory LDA-generated word cloud for the EU earlier. Once all the ‘sub-national’ plans are included, the U.S., Japanese and Chinese plans no longer fall in the same topic—the first two move toward showcasing pluralistic policy-making processes.

Image from LDA analysis executed by Amarda Shehu and Manpriya Dua

Second, EU regulations are often critiqued for stifling innovation. However, individual member states like Estonia and Czechia offer a counterpoint with high levels of innovation that may say something about state size and priority setting.

Third, still other states exhibit unique capabilities and opportunities. India promises to be a “garage” solution provider for innovation in mid-level states. The country’s India Stack, promoted by the government, has already garnered attention for combining a national-level data set with an applications and payments interface that has spurred a national start-up revolution. At the same time, India Stack raises concerns about data privacy and governance.

These examples show that innovation can occur in any country and is not limited to a particular political system or stage of economic development.

Overall, our research across the five most prevalent topics highlights patterns and granularities, which can be helpful for policymakers and scholars. Today, our use of computational AI to study AI policies is unique. The next phase of our research will tackle everyday and transformative questions with LDA and LLMs. We are also very interested in studying the effects of international organisations such as the OECD and the UN on national strategies.

Like other revolutionary technologies, AI brings transformation

Looking back, railways and telegraphs changed how we understood ourselves: the Industrial Revolution gave our work and private lives new meaning. Initially, the locomotive was seen as loco or a maddening influence in our lives. When the railways asked for standardized time zones, churches in the United States that set local time decried that machines were replacing God’s time. Neither love nor God died in people’s lives, but they may have been redefined. Our research argues that the thousands of pages of AI policy texts worldwide offer “entangled narratives” that provide intersections and distinctions between national plans. It’s always hard to validate, invalidate, or even construct an analysis of grand outcomes from such infrastructural entanglements, except to repeat John Maynard Keynes’ well-known maxim that in the long run, we are all dead.