A law for foundation models: the EU AI Act can improve regulation for fairer competition

The 30 November 2022 may have been a historical turning point. It was the day when OpenAI released ChatGPT, an AI Chatbot app based on the large-language model GPT-3.5, which is a special type of foundation model. Trained on massive quantities of data, foundation models have the potential to exhibit capabilities beyond those envisioned by their developers.

At first glance, they are nothing new. They date back around 2013 to the ‘Deep Learning Era’ and breakthroughs in image classification. Even the most recent large-language models, such as OpenAI’s GPT-4, Anthropic’s Claude or Google’s PaLM 2, work similarly to classic forms of machine learning: they try to predict the most likely next word over and over again, creating some knowledge by drawing on the internet.

What is, however, exceptional is that they have advanced tremendously over the last three years, exhibiting human-level performance on professional and academic benchmarks. They can also be adapted to a wide range of tasks, making them the perfect building block for thousands of downstream single-purpose AI systems. Integrated into more and more products and services, foundation models are proving they have huge potential. They are very good at the automation of tasks, personalised assistance, access to information, finding patterns and creating content, to name just a few areas. They could even help us to solve some of the biggest challenges for humankind, like resource scarcity and eliminating diseases like Alzheimer’s.

At the same time, they also make many ordinary tasks like coding or language translation significantly easier. Foundation models will likely become the new general-purpose technology, as defined by Lipsey and Charlaw, having a similar impact to money, iron, printing, steam engine, electricity or the internet eventually. History shows us that the rise of general-purpose technology will not only transform our societies, it often also restructures our economic systems.

US Tech Giants understood the huge potential of foundation models for their businesses but also the commercial threat of being left behind. As a result, the release of ChatGPT has triggered a global race for AI supremacy with almost weekly announcements of updated models and new applications.

All hype or a real threat to humanity?

Right now, there is certainly significant hype about foundation models. Some studies indicate that we should be cautious as some alleged emergent abilities may not materialise when using different metrics or better statistics.

Yet it is notable that a significant number of people, in particular from within the AI community, including Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, have stated that the advances with foundation models are happening too fast. Some have even gone so far as to state that they could lead to human extinction. Several globally leading AI experts have published articles, like the investor and co-author of the annual ‘State of AI‘ report Ian Hogarth, or signed open letters, for instance, from the Future of Life Institute or from the Center for AI Safety, arguing for a moratorium and in general for more caution.

What exactly is causing this fear? The declared goal of leading AI research laboratories such as Google DeepMind is to build Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), AI systems that would generally be smarter than humans. While there are different views on when the creation of an AGI will become feasible, the unifying concern of several leading AI experts is that foundation models could self-learn to code and take action on their own, initiating a loop of self-improvement and replication. Experts refer to model evaluations, indicating that some of today’s foundation models are already beginning to actively deceive humans and feature power-seeking tendencies.

Other hazards are already widely recognised. Emily M. Bender (University of Washington), Timnit Gebru (Distributed AI Research Institute), as well as Stanford’s Institute for Human-Centred Artificial Intelligence have long warned against a wide variety of costs and risks associated with the rush for ever more capable foundation models, recently complemented by work from the OECD.

The potential risks and hazards are becoming more and more concrete. Some include a flood of sophisticated disinformation (e.g. deep fakes or fake news) that could manipulate public opinion at scale, impossible for traditional approaches like fact-checking to counter; accidental representation, historical and other biases in the training data or in the foundation model itself that replicate stereotypes and could lead to outputs such as hate speech; copyright infringements; privacy issues; possibly significant job loss in certain sectors from AI replacing human tasks; hallucinations, meaning false replies articulated in a very convincing way; huge computing demands and associated CO2 emissions; and finally, the misuse of foundation models by organised crime or terrorist groups.

Even after intensive research and expert consultations across sectors, the situation remains ambiguous. For instance, Sébastien Bubeck, Microsoft’s ML Foundation Lead, admitted that his company cannot say with certainty whether their foundation models have already developed their own internal goals and pursue those by choosing the right outputs.

What seems clear is that foundation models play an increasing role in our life and that it is crucial to understand the full spectrum of potential opportunities and risks. Therefore, Ian Hogarth’s recommendation seems appropriate: we should concurrently and urgently tackle the already existing harms as well as the potential threats that increasingly powerful foundation models might pose in the future.

Why the AI Act is not helping: conceptual problems with the Commission’s 2021 draft

The text of the AI Act, as proposed by the European Commission in April 2021, did not explicitly cover foundation models. In fact, it may not even be able to do so on a conceptual level. The reason may be that, when the law was prepared around 2019-20, foundation models were still a niche in the field of AI. Back then, it looked reasonable to use a standard product safety approach based on the so-called ‘New Legislative Framework’ (NLF).

For years, the NLF worked very well for stable products such as a toaster or a toy with narrow intended purposes. But a foundation model has the potential to be deployed for countless intended purposes, many not initially foreseen in development. Without this key NLF element, the product safety approach cannot be applied to foundation models. As undefined and mouldable digital plasticine, they fall out of the scope of the AI Act.

A second, closely related problem is the European Commission’s use case approach. It assumes that the AI system respects boundaries and can be limited to certain risk classes. However, the latest foundation models can do many things and learn new tasks. They combine areas and recognise patterns we do not see as interlinked. This gives them the capability to come up with solutions that humans would never have thought of or would never have dared to do. Limiting the technology to concrete use cases that are prohibited (Article 5) or classified as high-risk (ANNEX III) is, therefore, too static for AI made in 2023.

A third and final conceptual problem with the AI Act proposal could lead to enormous disadvantages for European businesses. With the costs of training of GPT-4 at over $100 Million and the need for highly sophisticated components and infrastructure, only a few large technology firms (or start-ups financed by them) will likely be able to develop the most sophisticated foundation models. Other actors along the AI value chain could decide to settle for less cumulatively capable models with a more specific set of needs.

Alternatively, they could decide to become customers, choosing to refine or fine-tune certified models into single-purpose AI systems. However, by giving the foundation model an intended purpose and transforming it into a commercial product or service, downstream companies would be obliged to comply with the AI Act. They would become fully accountable for risks emanating from external data and design choices during the foundation model’s design stage.

Without the capacity to access and interpret core components of the pre-trained model, such as training data and evaluation gaps, those companies would risk facing penalties of up to 4% of their total worldwide annual turnover. The upstream provider of the foundation model would evade any responsibilities.

This is a well-known paradox: many EU laws in the digital field disproportionately affect European SMEs and start-ups. In this regard, also the European Commission’s AI Act proposal could benefit a few dominant upstream companies.

The European Parliament wants a holistic value chain approach

The good news is that both the Council as well as the European Parliament are aware of these conceptual problems and are eager to fix them. The text recently adopted by the Parliament features the most advanced approach to regulating foundation models. It adds an extra regulatory layer to the AI Act in the form of Article 28 b, fully in line with the 2019 OECD AI Principles that state that AI “should be robust, secure and safe throughout its lifecycle so that it functions appropriately and does not pose unreasonable safety risks”.

While the new article features a total of nine obligations for developers of foundation models, three stand out. The first is risk identification. Even though foundation models do not have an intended purpose, making it impossible to imagine all potential use cases, their providers are nevertheless already aware of certain vectors of risk. OpenAI knew, for instance, that the training dataset for GPT-4 featured certain language biases, as over 60% of all websites are in English. Article 28 b(2a) would make it mandatory to identify and mitigate reasonably foreseeable risks, in this case, inaccuracy and discrimination, with the support of independent experts.

The second is testing and evaluation. Providers are obliged to make adequate design choices in order to guarantee that the foundation model achieves appropriate levels of performance, predictability, interpretability, corrigibility, safety and cybersecurity. Since the foundation model functions as a building block for many downstream AI systems, Article 28 b(2c) aims to guarantee that it meets minimum standards. For instance, companies that draw upon PaLM 2 for their AI product should be certain that the building block fulfils basic cybersecurity requirements. Besides internal scrutiny, some model evaluation that involves independent experts seems reasonable.

The third is documentation. Modern AI is associated with the term “black box” for a reason. However, this should not mean a provider should be allowed to place a foundation model on the market without knowing its basic processes or capabilities. Drawing up substantial documentation in the form of data sheets, model cards and intelligible instructions for use, as required by Article 28 b(2e), will help downstream AI system providers to better understand what exactly they are refining or fine-tuning. Together, these three key pillars will make sure that the providers of foundation models fulfil limited but effective due diligence requirements prior to the release.

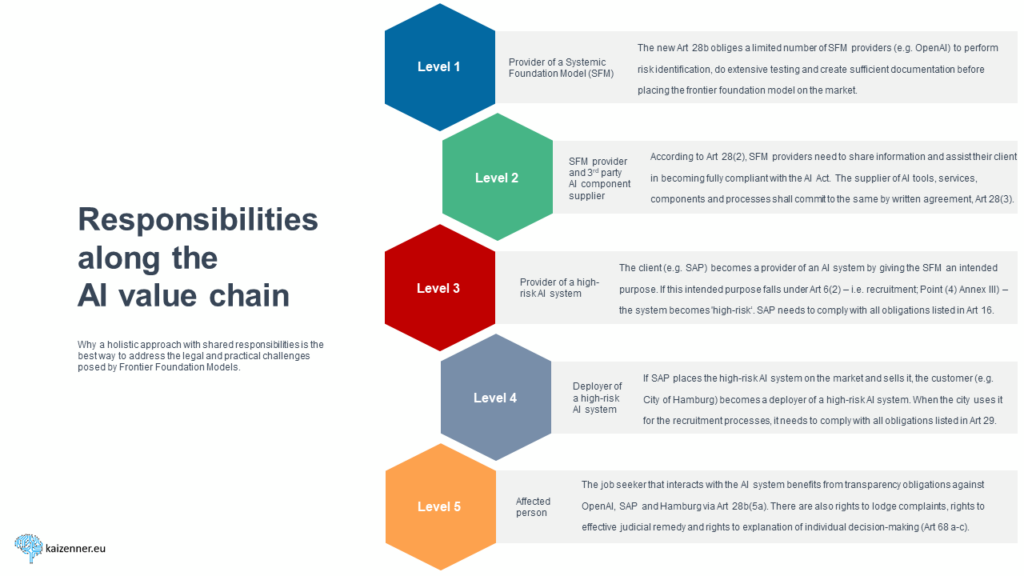

The European Parliament also has a holistic approach to addressing the challenges posed by foundation models along the entire AI value chain at four additional stages. The diagram below illustrates the Parliament’s approach using a hypothetical example centred on GPT-4.

To make sure that the European downstream service provider receives similar support from other actors that supply it with AI tools, services, components or processes, Article 28(2a) stipulates that the European downstream service provider and the AI component suppliers shall further specify the information-sharing duties through a written agreement based on model contractual terms published by the European Commission.

This second level should enable the European downstream service provider to fulfil all obligations of Article 16 (level 3) once it integrates GPT-4 in its high-risk AI system for human resources purposes (Annex III – point 4) and places it on the market.

When a European city buys and deploys this high-risk AI system to automate its online application processes (level 4), it has to fulfil the obligations of Article 29. Moreover, it needs to conduct a Fundamental Rights Impact Assessment (Article 29a). The affected person on level 5 (e.g. applicant for a vacancy at the city hall) benefits from the transparency obligations in Article 52 but also has several individual privileges, such as a right to an explanation of individual decision-making (Article 68c).

Together, these five levels make sure that many of the unique challenges posed by foundation models are addressed holistically along the AI value chain and that the regulatory burden of the AI Act compliance is fairly shared among the different actors, meaning that only the company that is in control of the model at a certain moment in time is responsible.

Some compliance requirements could stifle innovation in smaller companies and benefit the giants

As a swiftly drafted and fragile political compromise, there is room for improvement. Article 28 b was the result of a first brainstorming at the end of the political negotiations in the European Parliament. As a result, it lacks detail and clarity and will rely heavily on harmonised standards, benchmarking and guidelines from the European Commission.

The scope of Article 28 b represents the biggest problem. Without a better alternative, the European Parliament sticks close to the definition from the University of Stanford that describes foundation models as trained on broad data at scale, designed for the generality of output and adaptable to a wide range of distinctive tasks.

The AI community rightfully criticised this wording as overinclusive. The current Article 28 b would symmetrically apply all obligations to every foundation model provider, both large and small. To quote OpenAI’s CEO Sam Altman during the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee hearing on 16 May 2023: “It’s important that any new approach, any new law does not stop the innovation from happening with smaller companies, open source models, researchers that are doing work at a smaller scale. That’s a wonderful part of this ecosystem (…), and we don’t want to slow it down.”

Making compliance with Article 28 b mandatory for every actor that works on foundation models would further consolidate the market dominance of OpenAI, Anthropic, Google DeepMind and a few other companies. They already have a considerable lead in R&D. They also have the financial means and support and the know-how to become AI Act compliant rather quickly.

Even without additional regulatory burdens, it will still be hard for all companies outside this group to catch up with foundation model market leaders. For that reason, it seems reasonable to only apply Article 28 b asymmetrically to companies that have developed the most capable foundation models.

Narrowing the scope by focusing on systemic foundation models

The Digital Services Act shows a good way forward. Article 33(4) empowers the European Commission to adopt a decision that designates Very Large Online Platforms (VLOPs) and Very Large Online Search Engines (VLOSEs) based on certain criteria. The EU co-legislators could enact a similar approach to define Systemic Foundation Models in the AI Act. The term systemic would help to underline that it is only a small number of highly capable as well as systemically relevant foundation models that fall in the scope of Article 28 b.

Although established criteria and benchmarks have not yet been identified, it seems reasonable to follow a logic similar to that of the DSA. That law classifies platforms or search engines with more than 45 million users per month in the EU as VLOPS or VLOSEs. Research by Stanford University has identified a number of parameters that could be used to assess the degree of current foundation model provider compliance with the AI Act as approved by the European Parliament. Some of these same parameters might help to assess the degree to which a foundation model is systemically relevant. While certain parameters can only be identified post-deployment after the product has established itself on the market, others reflect technical characteristics that might be assessed pre-market. To name a few: the amount of money invested in the model; the amount of compute usage, like the number of floating point operations required to train the final version of the model; capabilities, such as the number of tasks without additional training, the adaptability to learn new distinct tasks, etc.; and the scalability of deploying the foundation model by the number of downloads on an open repository, inference API calls, etc. The pre-market parameters presumably correlate with the future systemic importance of a particular foundation model, and they likely also correlate with the ability of the provider to invest in regulatory compliance.

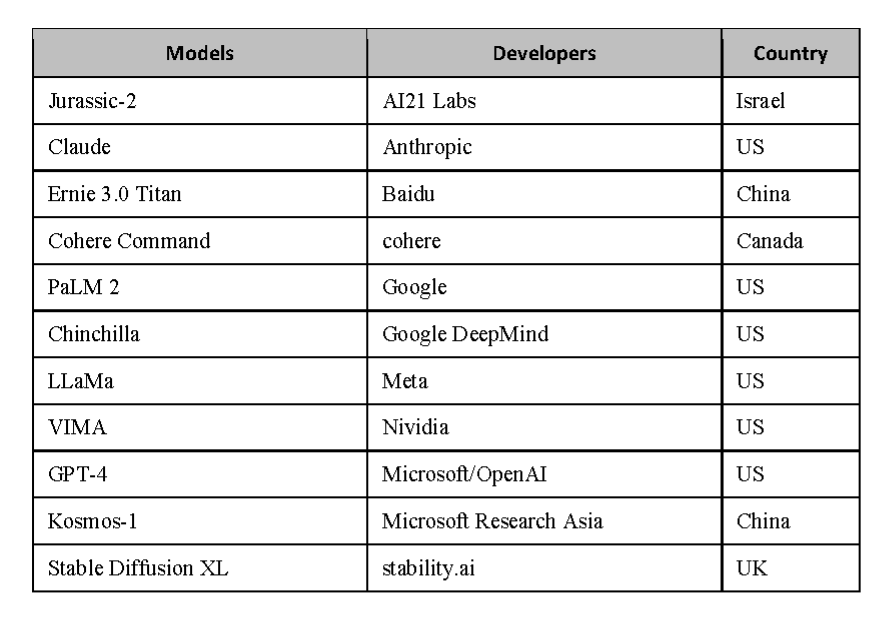

The non-exhaustive Table 2 indicates what a list of systemic foundation models could be if the European Commission, in close cooperation with the AI Office, would have assessed the status quo in June 2023.

This advanced version of Article 28 b would not only be more future-proof by taking into account valuable data from the market, but it would also allow for the list to be adjusted regularly in case the status quo changes. The Commission could remove models once they have lost their status as systemic foundation models in relative terms. Only the initial systemic foundation models at the very top of the AI value chain would face mandatory obligations but not the refined or fine-tuned versions of downstream providers.

The proposal also defuses the Parliament’s decision not to differentiate between distribution channels like API and Open Source. Foundation models under Open Source licences would only be designated if they have a commercial background and strong financial support from companies. Providers of foundation models that are not listed would only fall under the information sharing obligation of Article 28(2a), with the exception of the Open Source community (see Article 2(5d) together with Recital 12a-c). Protecting the latter at all costs is not only important for higher accountability. It is crucial to enable European companies to catch up with the non-European foundation model developers.

Data governance issues and foundation models

More issues within the European Parliament’s proposed Article 28 b deserve more elaboration, such as data governance. As demonstrated by studies, claims about the capacities of foundation models and their fitness for specific applications are often inflated in the absence of meaningful access to their training data. Copyright infringements and data protection breaches, in particular during large training runs, also remain a concern.

How can the quality and transparency of datasets be increased? Currently, reinforcement learning through human feedback (RLHF), sometimes done by so-called ghost workers prompting the model and labelling the output, remains the best method to improve datasets and tackle unfair biases and copyright infringements. Alternative ways towards better data governance, such as constitutional AI or BigCode and BigScience, exist but still need more research and funding. The AI Act could promote and standardise these methods. But in its current form, Article 28 b(2b) and (4) obligations are too vague and do not address these issues.

Greater clarity on oversight and practical incident reporting via IGOs

The question of when and whether to impose third-party oversight will be one of the most heated discussions during the trilogue negotiations. Is an internal quality management system, as proposed in Article 29 b(2f) by the European Parliament, sufficient? Or do increasingly capable foundation models pose such a systemic risk that pre-market auditing and post-deployment evaluations by external experts are necessary?

If one tends to support the latter view, these requirements would need to be scoped appropriately to protect trade secrets. And given the lack of experts, mandating sufficient data transparency to leverage the scientific community and civil society to pre-identifying risks and conformity would go a long way towards making external auditing more manageable.

Far easier in this regard would be mandatory systemic foundation model incident reporting that could draw on the comparable AI framework currently in development at the OECD. Internationally agreed frameworks, technical standards and benchmarks could not only pave the way to identifying the most capable foundation models but also improve issues with the requirement in Article 28 b(2d): the environmental impact of systemic foundation models. Their development demands enormous amounts of electricity and has the potential to create a large carbon footprint. Common indicators would allow for comparability and help to improve energy efficiency throughout the model’s lifecycle.

Let’s get international cooperation and competition right

Coming back to Ian Hogarth’s suggestion to tackle potential AI threats today that might or might not occur in the future. To be clear, AGI and the AI Act are not really a good fit. The remote danger of a rogue AGI would best be addressed at an international level. Close cooperation among governments and a joint research initiative on AI trustworthiness, interpretability and safety are two promising ideas. In particular, the success story of CERN shows that a permanent mechanism to pool national initiatives could help to gain a better understanding of the technology and leverage synergies. It could also lead to international standards and common forecasting. Another example to follow is the international cooperation on research for biological viruses that were considered a global systemic risk and, consequently, have been strictly regulated. Research in this area has at times even been globally halted by moratoria.

Whatever path is eventually chosen, providers of systemic foundation models should be incentivised to invest heavily in safety and security. Cyberattacks on cutting-edge AI research laboratories pose a major risk.

External security is not the only critical area. The internal safety of systemic foundation models is also crucial to keep them on track and prevent certain harmful outputs. While investment in these models skyrocketed in 2023, the funding for research in AI guardrails and AI alignment is still comparatively low. If the world is truly scared of AGI, shouldn’t this be the priority for spending?

What does all this mean for the EU’s approach to regulating foundation models? History shows that the rise of a new general-purpose technology marks the turn of an era. In terms of developing the top class of systemic foundation models, Europe is not likely to play much of a role. Actors from the United States and China are already too far ahead, have access to vastly more financing and have better digital infrastructures. However, the European Union faces a global AI community, including CEOs from many systemic foundation model companies, that call publicly for swift regulatory intervention. A genuine home game for Europe!

If the EU manages to adopt a targeted and balanced AI Act, it could not only mitigate the risks posed by systemic foundation models but also exploit their tremendous opportunities. At the same time, as a side effect, it could boost competition and reduce market dominance. Conversely, if the EU overregulates or does not act at all, it will solidify the existing market concentration, significantly handicap its own AI developers, and fail to install adequate safeguards. Confronted with those two scenarios, it seems to be an easy choice for the EU to make.

The views expressed in this article are personal and do represent neither the position of the European Parliament nor of the EPP Group.