AI openness: Balancing innovation, transparency and risk in open-weight models

In August 2025, OpenAI announced GPT-OSS, a family of open-weight models that provide public access to the trained parameters of a frontier-level AI system. This gives a new sense of urgency to the debate over how “open” artificial intelligence models should be. Some heralded the move as a victory for transparency and innovation. Others criticised it as a move that could accelerate malicious uses of advanced AI.

Not long after, the Global Partnership on AI (GPAI) at the OECD released a new report that helps governments understand openness in AI and navigate the complex trade-offs it entails. AI Openness: A Primer for Policymakers directly explores this tension.

By combining OpenAI’s release of GPT-OSS, the growing discussion around open weights, and the GPAI and OECD’s structured policy analysis, policymakers gain a clear picture of why AI openness matters, what benefits it promises, and what risks it brings.

Why “open source” AI is misleading and AI openness is a spectrum

The public often hears terms like “open-source AI” or “open AI models”, and the OECD/GPAI report explains why these expressions are imprecise. Unlike traditional software made up mainly of source code, AI models consist of multiple layers:

- Code, including training, evaluation and inference code

- Documentation, including evaluation results and model and data cards

- Data, including training datasets, evaluation data, and model weights and parameters that encode the system’s knowledge and guide how the model processes input to generate predictions or responses

Each of these can be opened or restricted to varying degrees, so AI openness is not binary but exists on a spectrum. A model’s inference code may be released openly, while its weights are closed. Another may share weights but with limited documentation or gated licences.

Moreover, licensing AI models and their components determines who can access, use, and share them. More permissive licences can encourage innovation by allowing widespread experimentation, but may offer fewer safeguards against misuse. Conversely, more restrictive licences can incentivise model development and investment but might limit broader collaboration.

For practical reasons, the OECD/GPAI report focuses on open-weight models. This narrower scope makes for a clearer, more actionable discussion of open-weight foundation models.

OpenAI’s GPT-OSS confirms a growing industry trend

There is an ongoing debate about the risks, benefits, and trade-offs of making powerful AI models and their components available to the public. The discussion gained momentum with the launch of several open-weight models, including Deepseek R1, OpenAI’s GPT-OSS, and Alibaba’s Qwen. OpenAI’s release of GPT-OSS is particularly emblematic of AI’s evolving landscape because it marks a significant shift for a company that, until recently, championed a closed model approach.

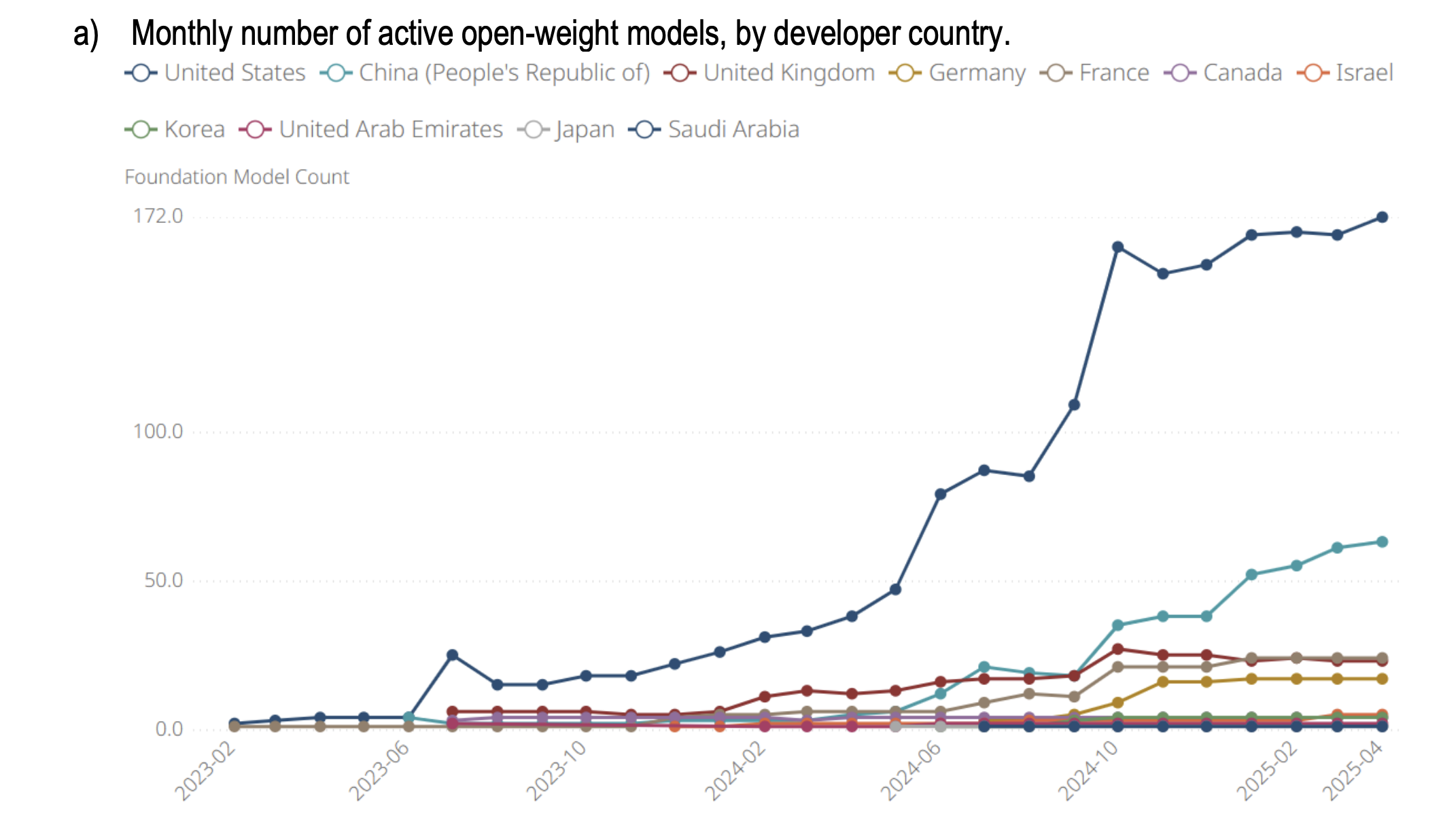

The United States, China and France are at the forefront of open-weight model

development, with the largest offerings coming from providers in the US, the Netherlands, and Singapore

Source: OECD.AI (2025), data from the AIKoD experimental database (internal), last updated 2025-04-30, accessed on 2025-05-14,

https://oecd.ai/.

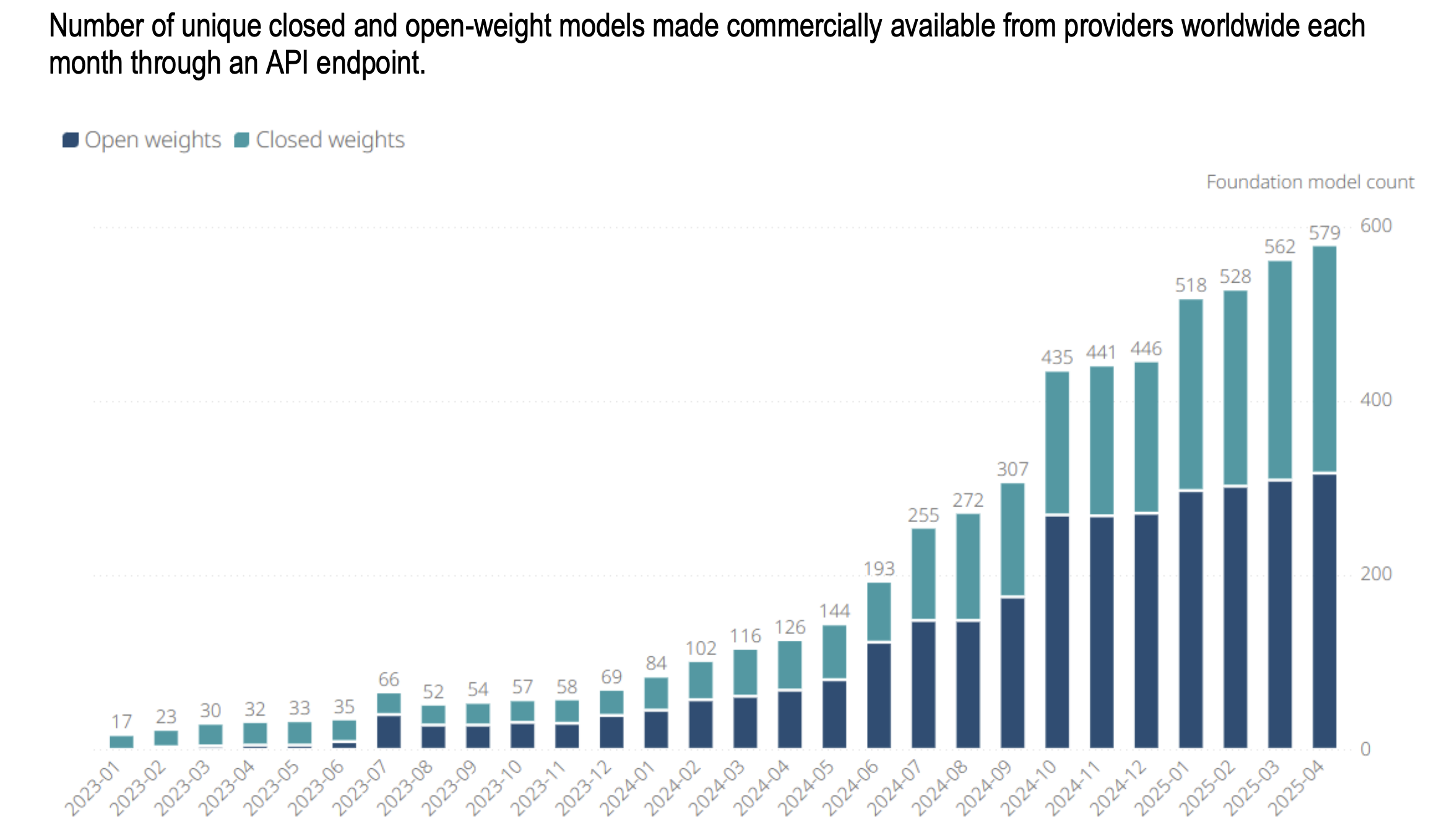

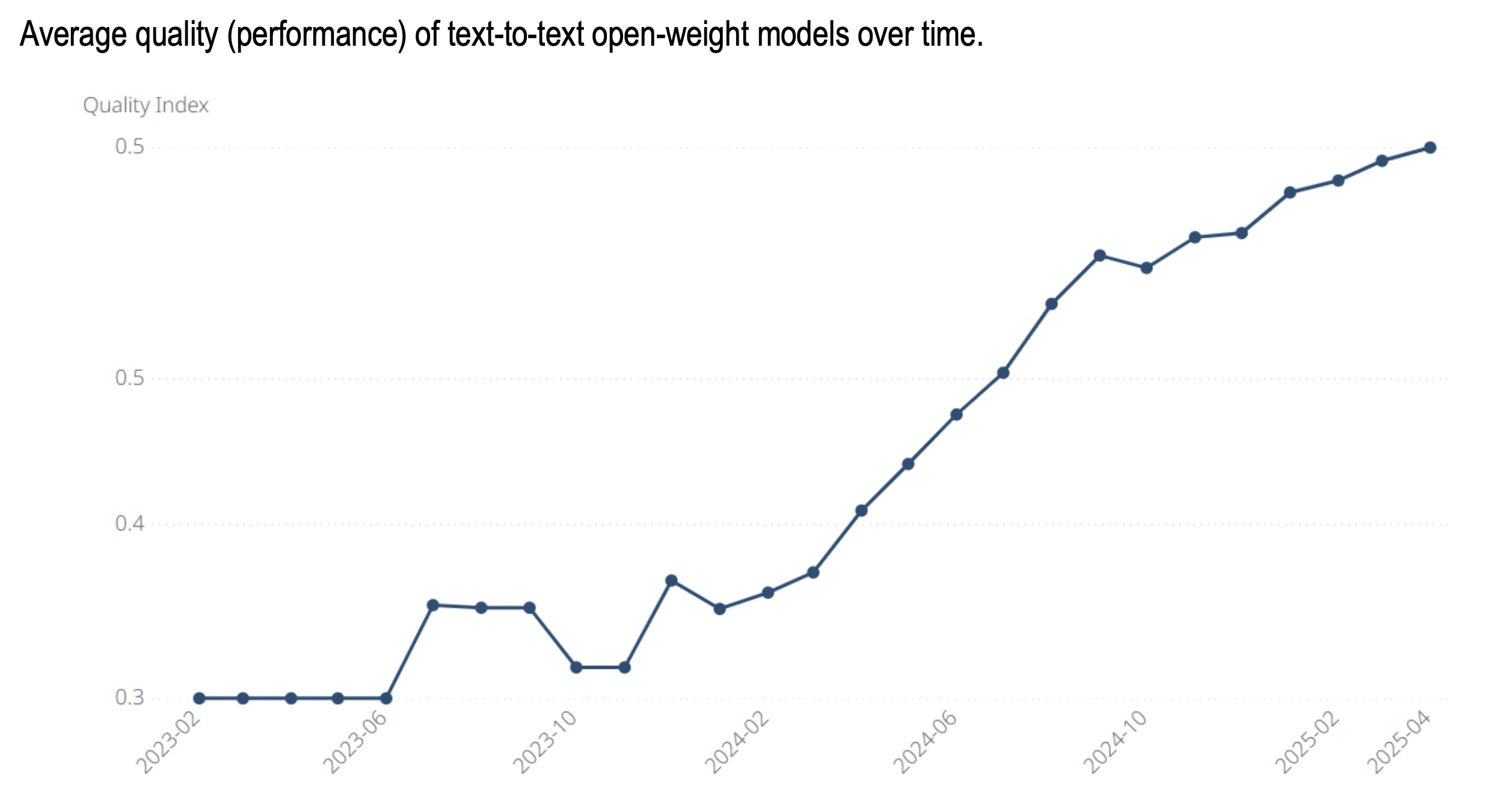

These launches align with a broader industry trend. According to the OECD/GPAI report, more than half of all commercially available foundation models in 2025 are open-weight. Primarily, actors in the United States, China, and France are leading these developments, reflecting both global competition and national strategies for technological sovereignty and global influence. What is more, open-weight models are increasing not only in quantity but also in quality: since early 2024, the average performance of open-weight models has improved rapidly.

The supply of foundation models has increased consistently, with open-weight models representing over half of the commercially available models

last updated 2025-04-30, accessed on 2025-05-14, https://oecd.ai/.

Significant gains in the quality of open-weight models

Source: OECD.AI (2025), data from the AIKoD experimental database (internal), last updated 2025-04-30, accessed on 2025-05-14, https://oecd.ai/.

The benefits of AI openness

These nuances and trends help to explain why openness in AI is compelling in many respects. The OECD/GPAI paper highlights many benefits:

Innovation and competition. Open-weight models lower barriers to entry. Start-ups, researchers, and even smaller governments gain access to advanced capabilities while making significant savings on compute and other resources to develop their own models. This fosters a more competitive market and allows a wider community to influence AI’s evolution.

Transparency and accountability. With open weights, independent experts can evaluate risks, biases, and vulnerabilities. This aligns with the OECD AI Principle of transparency and explainability, which encourages actors to create systems that can be understood and scrutinised.

Talent development. Universities and training programmes benefit enormously when students and practitioners can fine-tune and experiment with advanced systems. This builds AI literacy across societies, echoing the Principle of building human capacity and preparing labour markets by ensuring people broadly can participate in shaping AI.

Wider access, local adaptation, and sovereignty. Open-weight models empower a broader range of companies and governments to access, adapt and deploy AI locally, including in critical sectors where data is deemed too sensitive to share with third parties, such as healthcare and national security.

Diversity of use cases. By opening weights, developers around the world can adapt models to a wider range of applications, including those tailored to less common regions and cultural contexts, enhancing the relevance and inclusiveness of AI.

The risks of AI openness

But openness is not without its dangers. Once model weights are released, control over how the model is used is effectively lost, and safeguards can be circumvented. The OECD/GPAI report underscores several risks:

- Malicious use. Open-weight models can be misused for harmful purposes, like automated cyberattacks or creating intimate images without consent.

- Privacy and intellectual property concerns. Models may memorise sensitive or copyrighted material. Opening them up risks exposing this information without consent.

- Uncontrolled proliferation of risks. Modified versions of open-weight models can circulate widely, making it harder to track risks and enforce standards.

- Exposure of vulnerabilities: Releasing one model’s weights can expose weaknesses in other models and make it easier to trick them into generating harmful content.

- Potential risks: Some risks of releasing open-weight models – like misuse in biological or chemical fields – are possible but remain uncertain due to limited evidence.

Some of these risks are captured by the OECD AI Principle of robustness, security and safety, which calls for AI systems to be resilient and not cause unintentional or malicious harm.

Embedding marginal assessments in holistic risk management

The OECD/GPAI report presents a useful concept, that of marginal analysis. Decision makers should not ask, Are open-weight models good or bad? But instead, what additional risks or benefits emerge when model weights are shared, compared with keeping the model closed or using other tools like search engines?

For example, if a model’s capabilities are already widely accessible through closed commercial systems, the marginal risks of openness may be relatively small. Conversely, if a model introduces powerful new abilities with few safeguards, the risks of release are higher. This marginal approach helps move beyond polarised debates and towards nuanced, evidence-based decision-making.

However, marginal assessments depend on context: what counts as marginal risk or benefit may differ across countries and sectors. They also provide a relative measure of risk: repeatedly using more permissive baselines can slowly raise tolerance for harm (the “boiling frog” effect). Therefore, marginal assessments should not be conducted in isolation when deciding whether to release model weights but should be embedded in a broader risk-management strategy.

Responsible AI openness

As with most things AI, openness offers promise and peril. Managed well, it can foster innovation, broaden access, and enhance accountability. Poor management may accelerate misuse, undermine safety, and erode trust.

The OECD’s AI Openness: A Primer for Policymakers offers a compass for understanding this balance. For governments, researchers, and industry leaders, it is essential reading. And for the public, it provides reassurance that international institutions are working to inform the discussion and ensure AI develops in ways that serve society as a whole.

It also arrives at the right time. Without dictating a single solution, it provides policymakers and other decision-makers with a more informed lens for decision-making. By considering marginal risks, distinguishing between different dimensions of openness, and aligning with the AI Principles, governments can move beyond rhetoric and towards effective governance.

As the OECD AI Principles remind us, the goal is not openness for its own sake, nor secrecy for its own sake, but trustworthy AI that benefits us all.