Public AI: Policies for democratic and sustainable AI infrastructures

In late 2022, just as commercial AI labs were launching the first public-facing generative AI platforms, Mariana Mazzucato and Gabriela Ramos published an op-ed arguing for public policies and institutions “designed to ensure that innovations in AI are improving the world.” Otherwise, they warned, a new generation of technologies will develop in a policy vacuum.

Three years on, concentrations of power in AI have only deepened. A small group of dominant technology companies now controls not only most state-of-the-art AI models, but also the foundational infrastructure that shapes the field: GPUs used for AI training and inference, as well as cloud systems that host these chips.

As a result, cutting-edge AI remains in the hands of a select few actors, with limited orientation toward the public interest, public accountability or public oversight. However, a parallel trajectory of AI development suggests the possibility of building public AI infrastructures and services.

Public compute initiatives are the first step, aimed at securing the AI development capacity needed. These include the National AI Research Resource (NAIRR) pilot in the United States, European AI Factories, Canada’s Sovereign AI Compute Strategy, and Open Cloud Compute in India, all of which aim to provide the necessary compute infrastructure.

In parallel, open-source and open-weight AI models have been released by a broad range of actors: non-profit institutions like the Allen Institute for AI, research centres like the Barcelona Supercomputing Center, and commercial actors like Mistral. And the release of DeepSeek R1 showed that high-capability AI models can be built with less compute than that used by many US AI labs, and shared openly.

Finally, proposals for new institutions and coordination frameworks include international research collaboration (CERN for AI) and the provision of AI services as a public utility (Public AI Company).

A policy vision for public AI

These initiatives demonstrate the potential of alternative AI systems and the need for public investments and policies to enable more sustainable scaling. Instead of rashly joining the AI race, policymakers should explore AI strategies and chart paths for public AI development.

A recent report from Bertelsmann Stiftung and Open Future lays out the argument for public AI policies that orchestrate AI development in the public interest, with AI systems developed under transparent governance, public accountability, equitable access to core components and a clear focus on public-purpose functions. Such policies can serve to democratise AI by ensuring democratic governance over AI systems.

The definition of public AI builds on the broader concept of public digital infrastructure, which refers to digital infrastructures designed to maximise public value. It is a policy framework that shifts from maximising technological and economic growth to the social relevance of making AI systems truly public. Public AI infrastructures combine three essential characteristics:

- Public attributes: Public infrastructure would provide unrestricted access to open, interoperable, auditable, and transparent AI components.

- Public functions: These infrastructures would support stated public-interest goals and the common good by enabling downstream activities that deliver public benefits, supporting innovation, and safeguarding user rights and social values.

- Public control: The AI stack would be under democratic control with mechanisms for collective decision-making and accountability. This implies public oversight, funding, and/or production of AI infrastructures.

The AI stack and its layers

AI policies must account for bottlenecks and concentrations of commercial power. To conceptualise these challenges, it’s helpful to think in terms of a layered AI stack – similar to the internet stack used in internet governance.

The AI stack has three core layers: compute, data and models. The compute layer refers to the physical and software infrastructure that enables AI development and deployment, including specialised processors, software frameworks, and data centres. Software can also be understood as a cross-cutting layer that spans the entire AI stack. The data layer involves the storage, processing, and transfer of datasets used in the pre- and post-training phases.

AI models are typically deployed as cloud-based services. The application layer sits on top, with models embedded in user-facing applications. Running these requires specific computing power, called inference compute.

To generate meaningful public value, complete policy frameworks should address not just compute provision but also data governance and model development.

Technology companies often build strategies around a stack concept, aiming to control key layers. A public approach focuses on control and orchestrating various actors and components to achieve public-interest goals.

Public AI doesn’t entail public control of the whole stack. Private and civic actors can contribute with proper incentives. For example, public AI initiatives can benefit from open-source AI models. The key challenge lies in identifying effective public interventions as dominant AI firms consolidate control over infrastructure stacks.

The goals and principles of public AI policy

The goal of public AI policy should not be to create infrastructures that compete with commercial systems. Instead, it should prioritise reducing dependencies and generating public value. In other words, it should build normative alternatives. A report by the Ada Lovelace Institute notes that “the aim of these policies should not simply be to build more and faster, … public compute investments should instead be seen as an industrial policy lever for fundamentally reshaping the dynamics of AI development”.

Without public AI infrastructure, all deployed AI solutions will be built with commercial logic in mind and will depend on monopolistic AI companies. This is especially problematic when solutions for the public sector are considered, as AI services are deployed in public health care or education. Public AI approaches can also fulfil the goals of strategies aimed at strengthening endogenous AI capacity, such as the Continental AI Strategy adopted by the African Union.

These alternative AI systems need to be governed in a way that secures public interest. And while public AI builds on the vision of open science and open source development, it espouses a broader range of principles. These include:

- Directionality and purpose: Public AI must be developed with a clear purpose, focusing on meeting the real needs of people and communities – and not just scaling technological development.

- Commons-based governance: Datasets, software, and key AI components should be stewarded as commons, encouraging open access while establishing democratic oversight and collective stewardship.

- Open release of models and components: Key components of public AI systems should be released as digital public goods under open source licenses.

- Conditional computing: Conditionalities for public procurement and compute use should ensure that resources serve public-interest goals.

- Protecting digital rights: Public AI systems should set high standards for privacy, data protection, copyright, freedom of expression and access to information.

- Sustainable AI development: AI systems should promote environmental sustainability, fair resource use and long-term societal benefit.

- Reciprocity: Actors benefiting from public AI resources should adhere to these governance principles to prevent the privatisation of public value.

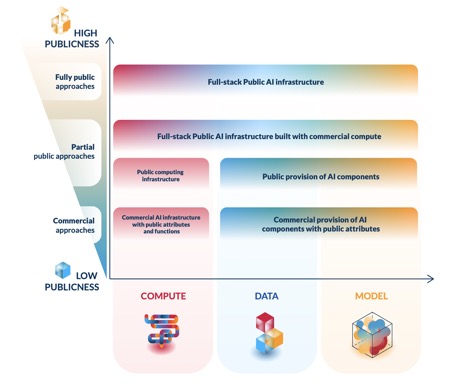

Gradient of publicness of AI systems

Public AI policy should increase the degree of publicness in AI systems rather than seek fully public ones. This means prioritising interventions across the AI stack that generate public value and minimise dependencies on commercial providers. Public AI initiatives can be positioned on a gradient based on three properties of public digital infrastructure: attributes, functions and control.

This approach recognises that some dependencies are unavoidable, particularly on commercial compute providers, cloud oligopolies, and chip design and manufacturing oligopolies. It provides six distinct levels ranging from commercial provision with public attributes to full-stack public AI infrastructure.

While most public AI initiatives will remain dependent on the compute layer, there are fewer dependencies for data and models. At these layers, public provision faces fewer obstacles, making it easier to build highly public AI infrastructures.

AI systems can be made more public by orchestrating actions across various layers. Such “full stack” approaches seek synergies between stack layers. For example, investments in public compute are more effective when combined with developing open source AI models that power solutions based on these models.

Three pathways to public AI

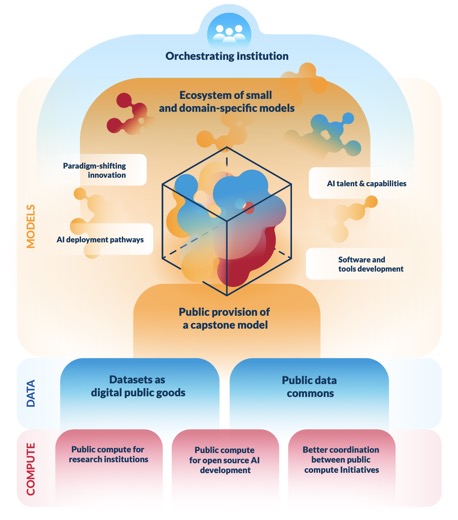

The white paper outlines three complementary pathways to developing public AI infrastructure, each targeting a different layer of the AI stack: compute, data and models.

The compute pathway aims to reduce dependence and, where necessary, develop publicly owned infrastructure. Our recommendations prioritise targeted, strategic investments over replicating massive commercial spending patterns. This includes securing compute for open source AI development and research institutions, reducing the “compute divide” by ensuring cutting-edge AI research isn’t confined to private labs. Improved coordination between public compute initiatives moves beyond narrow sovereignty-first approaches and instead promotes global, cross-border cooperation.

The data pathway emphasises the creation and sharing of high-quality datasets. First, datasets designed as digital public goods build on foundational Open Data sources like Wikimedia and Wikidata. Efforts should shift from releasing as much data as possible to intentionally creating high-quality, purpose-built datasets, with a focus on filling gaps in training data for most world languages. Second, public data commons are needed to protect against value extraction while ensuring equitable access. These forms of data governance suit sensitive data where rights must be protected or economic factors in dataset creation must be considered. Data commons for AI means stewarding access through clear sharing frameworks, ensuring collective governance with communities and trusted institutions, and generating public value through mission-oriented goals.

The model pathway to public AI should foster an ecosystem of open-source AI models. Public policies and funding should support the development of highly capable “capstone” models that serve as foundations for a public-interest AI ecosystem. Public model development should aim for permanently open, democratically governed generative AI models as close as possible to the frontier of capabilities. Such models should serve as both flagship public assets and foundations for broad-based research, innovation, and deployment.

Secondly, public AI initiatives should develop small, domain-specific models tailored to specific policy goals and community needs, such as models for public-sector solutions. Work on such alternative models allows limited public funds and compute resources to target specific interventions.

From sovereign AI to multilateral collaboration

We need to move beyond “sovereign AI” strategies that treat AI as a national competition, where success is measured simply by GPU acquisition. Especially since most national AI efforts cannot compete at the frontier of AI development. Instead, multilateral collaboration across national AI efforts is needed. The development of open-weight AI and other digital public goods provides frameworks for such collaboration.

Public AI strategies should leverage public compute infrastructure to build a holistic ecosystem that includes data commons, open-source components, and capstone AI models. This approach enables public-interest solutions while reducing dependence on proprietary commercial infrastructure.

AI policy should not be driven by arms race mentality or hype. It should focus on building useful, practical AI while supporting research into sustainable architectures. The aim is not to dismiss AI’s potential, but to ensure development is sustainable, open, and democratic.

The ultimate goal should be to provide AI technologies as a globally accessible digital public good.