When it comes to AI incidents, safety and security are not the same

The OECD common reporting framework for AI Incidents is progressing fast to become the basis for a standard for AI incident reporting, with ETSI, and ISO considering building upon it. The framework significantly enhances the ability to share data about AI incidents and hazards within the AI ecosystem.

However, there is an obstacle that could block the framework’s broad adoption by the security community: a lack of information to better handle cybersecurity issues.

| Non-security AI Incidents – Accidental | AI Security Incidents – Intentional (caused by an attacker) |

| “Traffic Camera Misread Text on Pedestrian’s Shirt as License Plate, Causing UK Officials to Issue Fine to an Unrelated Person”. AIID“Alexa Recommended Dangerous TikTok Challenge to Ten-Year-Old Girl”. AIID“Character.ai Chatbot Allegedly Influenced Teen User Toward Suicide Amid Claims of Missing Guardrails”. AIID, AIM | “AI Face-Swapping Allegedly Used to Bypass Facial Recognition and Commit Financial Fraud in China,” AIID, AIM“‘Jewish Baby Strollers’ Provided Anti-Semitic Google Images, Allegedly Resulting from Hate Speech Campaign” AIID“Alleged Fraudulent Prompts via AIXBT Dashboard Led Purported AI Trading Agent to Transfer 55.5 ETH from Simulacrum Wallet” . AIID |

After decades of hard-fought advancements, the security community broadly knows what a good process looks like. However, they are still figuring out how to best address security incidents related to AI. One challenge is to obtain information about how an attacker may produce harmful events, i.e., incidents, which is central to security processes. Without information about the capacity malevolent actors have to exploit a vulnerability, the security community cannot weigh the benefits of disclosing weaknesses against the cost of empowering attackers with greater knowledge.

To speed up the adoption of the common incident expression, it would be helpful to (a) explicitly set aside security incident reporting or (b) provide extensions to the OECD framework that would be conditional and necessary for AI security reporting. The latter is in line with the flexibility that the OECD framework provides and would benefit from the international consensus that the OECD framework has gathered.

Let’s have a more detailed look.

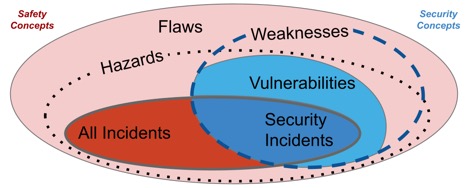

Square and round pegs

To be clear, the practice of “security” may be viewed as a subgroup of “safety” with the additional challenge of addressing malicious actors. Despite being part of the broader “safety” ecosystem, recent standardisation efforts have exposed tensions between the product safety and security communities. In particular, cybersecurity practitioners entering into product safety spaces can become frustrated with insufficient attention to adversarial threats. Although adversarial threats can be an element of product safety, not all AI incidents involve adversaries. The OECD framework’s focus on everything from deprivation of fundamental human rights to injuries related to robotics is much broader than the specific requirements of security incidents.

| Safety communities and the problems they address | |||||

| Someone or something could be impacted… | …by people wanting to do bad things… | …involving an AI system… | …that is attacked… | …or is used to attack. | |

| AI Safety | ✓ | Maybe | ✓ | Maybe | Maybe |

| AI Security | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Maybe |

| Computer/ Cybersecurity | ✓ | ✓ | Maybe | Maybe | Maybe |

| Offensive AI | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Maybe | ✓ |

>> REPORT: Towards a common reporting framework for AI incidents <<

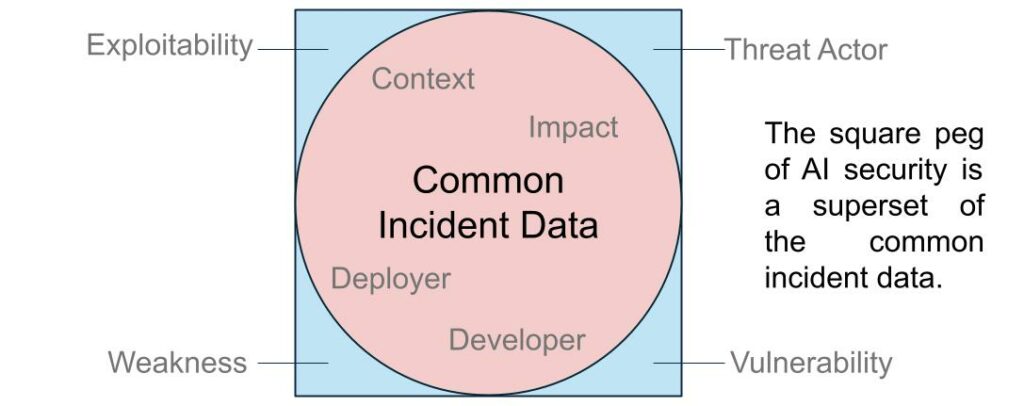

The common data useful across all AI incidents are necessary for AI security incident reporting, but so are others. Attempts to force cybersecurity norms into non-security incidents have proven equally problematic. When security professionals require detailed attack documentation for human rights or robotics incidents, they risk obscuring the essential elements that make the OECD framework valuable for broader AI incident reporting. Just as a leaf of lettuce can kill without anyone attacking the food supply, AI products can kill without any bad intentions.

Unfortunately, the square peg of security methodology doesn’t fit neatly into the round hole of common incident reporting. Still, the common expression of the OECD framework includes necessary information for assessing the impact of AI security incidents.

We can and should collect the fields of the common incident expression for AI security incidents, but we should also look to understand what is not there that facilitates cybersecurity.

Understanding the distinction between common AI incidents and security data

The first thing to understand is that while all security incidents are harm events, not all harm events are security incidents. For example, a facial recognition system that systematically misidentifies people with certain facial features as non-human may harm people with those features. But people may also modify their features to become invisible to the same cameras deployed as a home security system. In the latter case, where there is deception, the harm and the processes for mitigating its recurrence are dependent on how easily people might modify their features and how well-known the exploit is. On a technical level, it also depends on how commonplace the security camera is and if other products share the same components. Today, these aspects fall outside of the scope of the OECD’s incidents framework.

The presence of malicious actors in security incidents necessitates collecting and distributing additional data within a responsible disclosure process. These additional requirements are not bureaucratic overhead; they are essential for preventing future attacks and building collective defence capabilities. The security-specific data could help determine how companies respond to an incident. In Cybersecurity, it is recognised that if a vulnerability is widely known to attackers, it can be widely communicated. But if very few people know about the vulnerability, the balance of equities tilts towards keeping the vulnerability secret until systems can be patched.

Current standardisation efforts for the broader class of AI incidents do not address these security needs. They lack the specific elements required for effective AI security incident management, frustrating AI security professionals.

A path forward – together or apart

Explicitly acknowledging and accommodating these differences is the obvious solution. We need extensions to the OECD Framework that specifically address AI security reporting requirements. These extensions should include fields for vulnerability classification and other security-specific elements that don’t apply to all incidents.

Alternatively, implementations of the OECD framework could explicitly flag AI security incidents and allow for parallel processes tailored to security needs while maintaining compatibility with the broader framework. This approach would let security and product safety processes coexist without forcing either community to compromise essential practices. Even when operating separately, the uncertainty of whether an incident evidences a vulnerability means clear escalation paths from “AI safety incident” to “AI security incident” are necessary.

How we structure these frameworks is not just a taxonomic exercise; it will determine whether organisations can effectively learn from incidents. It will influence how AI security teams share threat intelligence and whether non-security incidents are forced into security-oriented reporting structures ill-adapted to product safety and other needs.

The cultural divide between security and safety communities reflects real differences in priorities, methodologies, and requirements. Rather than treating this divide as a problem to be papered over, we should recognise it as a reflection of genuine needs that must be addressed. Only by explicitly acknowledging these differences can we build incident reporting frameworks that serve both communities effectively and, ultimately, make AI systems safer and more secure for everyone. The OECD AI incidents reporting framework offers a solid foundation for different communities to build upon, allowing each to address their unique needs while using a common and interoperable reporting base.

Acknowledgements

This blog post benefits from collaborations with many people and projects. We would like to specifically thank John Leo Tarver, Bénédicte Rispal and Daniel Atherton for their feedback and contributions to this specific blog post, along with Lukas Bieringer, Nicole Nichols, Kevin Paeth, Jochen Stängler, Andreas Wespi, and Alexandre Alahi, with whom we collaborated in authoring Position: Mind the Gap-the Growing Disconnect Between Established Vulnerability Disclosure and AI Security.