Can mid-sized economies come together to build frontier AI?

Conventional wisdom presents mid-sized economies with two options for accessing advanced AI: rely on American or Chinese systems, or fall behind. Neither choice preserves the technological sovereignty that countries increasingly see as essential. But there is a third path we explore in detail in a recent memo. Collectively, nations outside the US-China duopoly possess substantial computing infrastructure, a majority of the world’s top researchers, and the growing political will to create a third path. The question is whether they can come together to make it work.

The dependency dilemma

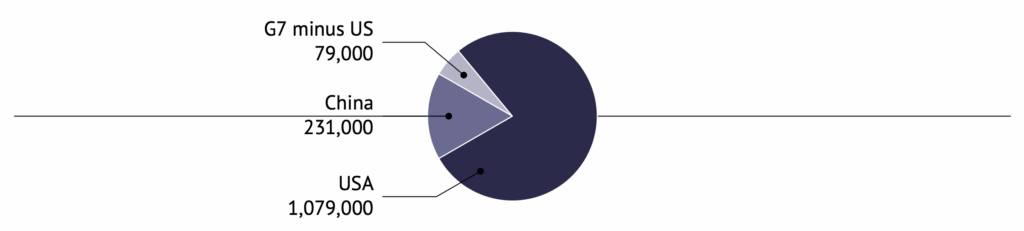

Developing frontier AI is now an activity confined mainly to two countries: the US and China. American tech giants have announced AI investments totalling more than $300 billion this year alone. Chinese companies are following with commitments approaching $100 billion. US firms control nearly three-quarters of the world’s AI compute power, while China holds a distant second place at 15%. Europe is at 5%.

Figure 1: Global Distribution of AI Compute in October 2025 (H100 equivalents)5

This concentration creates two distinct compute divides: one between nations, and another between academic institutions and private laboratories within those nations. Even in countries with substantial overall capacity, university researchers often lack access to the computational resources that corporate labs deploy routinely.

Relying on foreign AI systems means accepting that access can be restricted or withdrawn at any time, that data protection depends on foreign law, and that the worldview encoded in these systems comes from design decisions made in Beijing or San Francisco. Recent cloud service outages highlight how reliance on concentrated digital ecosystems creates vulnerabilities even in peacetime.

Limiting AI adoption to avoid dependency carries more and greater risks. If cutting-edge AI enables transformative advances in how economies produce, sciences discover, and militaries operate, countries that hold back may find capability gaps that grow and compound over time.

This is the dependency dilemma: dependency invites exploitation, but restraint invites weakness. For countries outside the small circle of frontier AI developers, neither option preserves the sovereignty and strategic autonomy they value.

Multinational cooperation could be an escape from this dilemma. It is not guaranteed, but it is plausible.

The resources for a third option already exist

The good news is that mid-sized economies collectively possess substantial AI development capabilities. Indeed, the pieces for a multinational partnership already exist.

With regards to talent, of the 100 most-cited AI researchers globally, 87 originate from or currently work in countries outside the United States and China. Many of these prominent AI scientists have voiced discomfort with the current model of rapid development behind closed doors, accountable to shareholders rather than the public. An inspiring multinational project backed by adequate resources and a commitment to ethical development could attract significant talent that might otherwise head to Silicon Valley.

On infrastructure, substantial compute capacity is coming online, and the European Union has committed over €20 billion to AI computing efforts. Europe’s AI Factories and public supercomputers are deploying significant resources. Germany’s Jupiter supercomputer, with 24,000 GPUs, is already operational. France’s exascale Alice Recoque system is scheduled to arrive in 2026. Five Gigafactories will deliver over 100,000 specialised AI chips each by 2027.

No single mid-sized country can match the scale of initiatives like OpenAI’s Stargate project. But the coordinated deployment of existing and planned capacity across multiple nations could support frontier-scale development. The infrastructure is being built; the question is whether it will be used collectively or in fragmented national silos.

Multinational AI cooperation in practice

Real initiatives are already demonstrating that international AI cooperation works.

The Trillion Parameter Consortium brings together major supercomputing centres and research laboratories from around the world, including those from the United States. Its mission is to develop and use very large AI models for scientific and engineering purposes.

Rather than each institution building isolated capabilities, members pool expertise and infrastructure across borders to tackle challenges no single organisation could address alone. This is a good example of the kind of cooperation that could eventually support frontier AI development. The TPC demonstrates that effective international AI cooperation need not be antagonistic toward dominant powers. Instead, it can focus on public-interest use cases and distributed governance structures that prevent dangerous concentration of transformative capabilities in either public or private hands.

Another example is the collaboration between GENCI (France’s national high-performance computing agency) and the University of Bristol, which will focus on distributed and federated learning techniques. Their approach allows sovereign compute centres to contribute to shared training workflows while maintaining complete control over their datasets and infrastructure. In fact, sustained R&D investment in these new architectures and capabilities is something countries serious about sovereignty-preserving AI cooperation should prioritise, given their central role in enabling capacity pooling.

Why does this matter? Many governments worry that international AI collaboration requires the transfer of sensitive data to foreign systems. The Bristol-France model proves these concerns need not be obstacles. With federated learning, the data never leaves national boundaries. This architecture enables pooling compute capacity and developing shared AI capabilities without centralising sensitive information.

The hidden economics of AI development

Existing partnerships suggest that cooperation is technically feasible. But why would it be economically attractive?

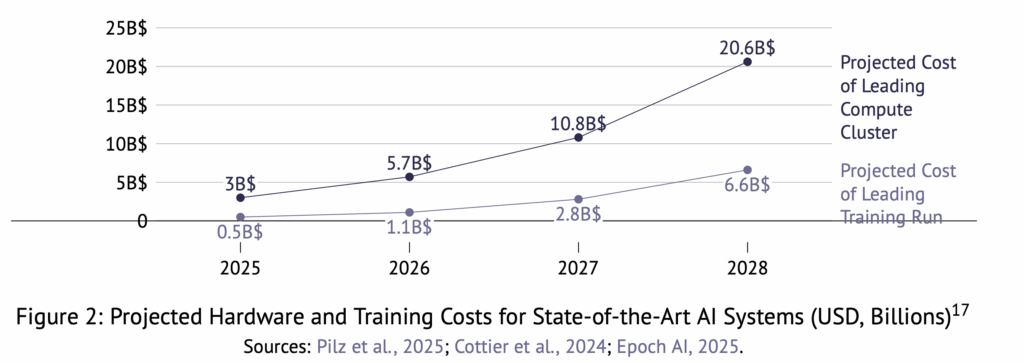

Training an AI model is like writing a book: it requires a massive, concentrated effort up front. It is the process of teaching the model to understand language, reason about problems and generate useful outputs. Teams of researchers work for months, consuming enormous computing resources, to create a single model. The costs are fixed regardless of how many people eventually use it. Today’s leading AI models cost hundreds of millions of dollars to train, and projections suggest costs could reach several billion dollars within a few years.

Inference—actually using the trained model to answer questions, generate text, or perform other tasks—is more like printing copies of that book. Costs scale with the number of users and can be spread across countries based on demand. Each nation needs inference capacity proportional to its own usage.

Figure 2: Projected Hardware and Training Costs for State-of-the-Art AI Systems (USD, Billions) Sources: Pilz et al., 2025; Cottier et al., 2024; Epoch AI, 2025.

This distinction matters enormously for international cooperation. The expensive, concentrated work of training is precisely where pooling resources delivers the greatest benefit. Countries can share the heavy lifting of creating powerful AI models, then deploy them independently for their citizens and industries. Sharing training costs while maintaining independent inference capacity gives countries the benefits of scale without sacrificing control over sensitive applications.

The economics here differ fundamentally from many other technologies. Unlike manufacturing, where scale economies often mean centralising production, AI development allows for distributed collaboration during training and decentralised deployment afterwards. This creates natural opportunities for international partnerships that simply don’t exist in many industries.

Scale isn’t everything

Recent developments suggest that frontier competitiveness comes from how resources are deployed, not just their quantity. DeepSeek and Mistral achieved performances comparable to leading models while spending less, through architectural innovations and strategic focus.

A multinational partnership could pursue strategies different from those of profit-driven corporate labs. Goals like sovereignty, trustworthiness for sensitive government applications, and democratic legitimacy suggest investing in areas where simply scaling up isn’t enough. Advances in reliability, reasoning, and ethical AI behaviour may prove more valuable to participating nations than racing to match every frontier benchmark. Indeed, many high-value industries and the most sensitive applications demand trustworthy, auditable systems over opaque frontier capabilities.

Learning from successful precedents

Large-scale international research collaborations have succeeded before. CERN demonstrated that European nations could pool resources to lead the world in particle physics and generated enormous spillovers in computing and other fields. Airbus showed that cooperation could challenge American dominance in aerospace. ITER is attempting to do the same for fusion energy.

These precedents suggest several principles for AI cooperation. A semi-distributed structure with a few core facilities can leverage members’ comparative advantages and create the critical mass of talent that drives innovation. Equitable sharing of costs and benefits through funding, in-kind contributions, and licensing arrangements keeps all members invested in the project’s success. Importantly, any successful initiative will require agile governance, as AI’s pace demands more streamlined approaches than those achieved by some previous multinational initiatives.

Timing is critical

The window for action may not stay open indefinitely. Current frontier training costs remain within reach of coordinated mid-sized economies. But barriers to entry, such as compute monopolies, talent concentration, and entrenched geopolitical leverage, will likely grow. Countries that wait risk finding themselves permanently on the outside.