From PISA to AI: How the OECD is measuring what AI can do

Does anyone really know what AI can and cannot do? Amidst all the hype and fear surrounding AI, it can be frustrating to find objective, reliable information about its true capabilities.

It is widely acknowledged that current AI evaluations are out of step with the performance of frontier AI models, particularly for newer Large Language Models (LLMs), which leading tech companies release at a fast pace. We know ChatGPT can outperform most students on tests like PISA and even graduate students on the GRE, but can AI handle human tasks like managing a classroom of rowdy kids, placing a tile on a roof or negotiating a contract for a service?

The natural response may be to turn to specialist benchmarks developed by computer scientists. However, no one outside a small group of AI technicians understands benchmark results and their actual significance. When OpenAI’s GPTo1 scores 0.893 on the MMLU-Pro benchmark, does this mean AI is ready to be deployed throughout the economy? What sorts of human abilities can it replicate? The truth is that no one really knows.

The issue is garnering attention from AI researchers themselves. This year, the Stanford AI Index Report dryly notes that “to truly assess the capabilities of AI systems, more rigorous and comprehensive evaluations are needed”. Ex-OpenAI and Tesla AI researcher Andrey Karpathy bluntly described “an evaluation crisis”, while Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella dismissed many capability claims as “benchmark hacking.”

Policymakers also note the need for trusted measures of AI capabilities. The EU Artificial Intelligence Act mandates regular monitoring of AI capabilities. For their part, the OECD Council’s AI Recommendation and the 2025 Paris AI Summit emphasise the importance of understanding AI’s influence on the job market.

Despite all the attention, a persistent gap remains: there is no systematic framework that comprehensively measures AI capabilities in a way that is both understandable and policy-relevant.

To address this gap, the OECD’s AI and Future of Skills team has developed a framework for evaluating AI capabilities. The report Introducing the OECD AI Capability Indicators, released on June 3 presents this approach for the first time alongside its resulting beta AI Capability Indicators.

For 25 years, the OECD has tested the abilities of 15-year-olds in subjects deemed essential for their success in life as part of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). By combining decades of experience in comparative student assessment with the expertise of AI researchers, we have developed a methodology to assess whether AI can replicate the abilities considered important for humans in schools, the workplace, and society. Given its ability to leverage these two perspectives, we believe our organisation is uniquely positioned to inform policymakers about what AI can and cannot do and to lay the groundwork for the development of a systematic battery of relevant and valid AI assessments in the future: a PISA for AI.

The OECD AI Capability Indicators in a nutshell

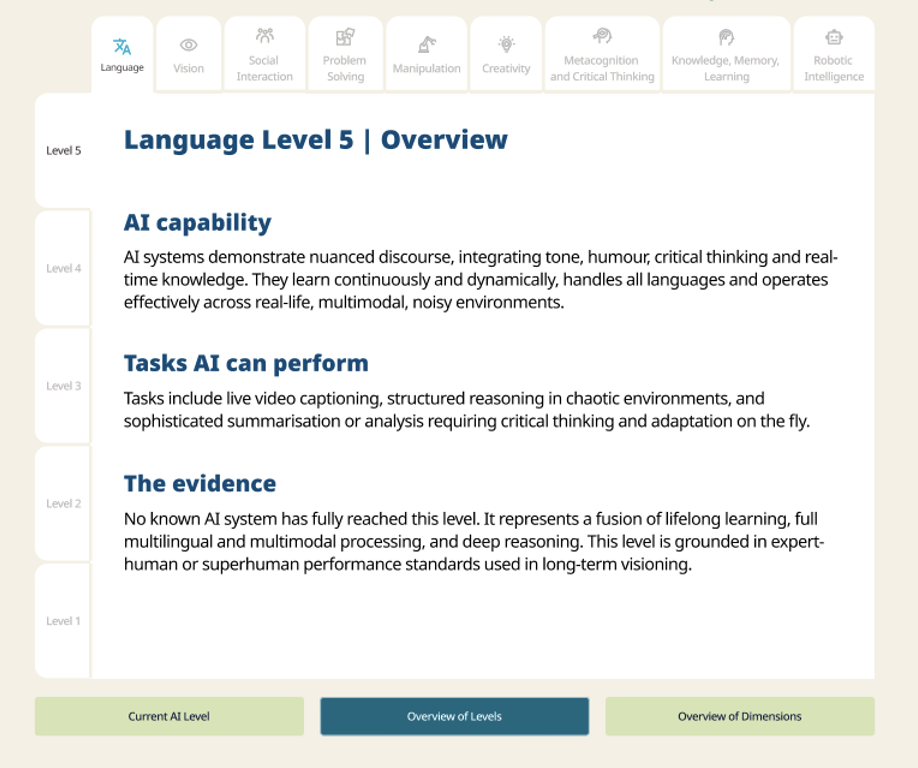

The indicators are a 5-level scale. Each level describes the sorts of capabilities that AI would need to perform human tasks, with the easiest ones at the bottom of the scale and the hardest ones at the top. The indicators have been developed across nine capability domains, such as Language, Creativity and Reasoning, that represent the full range of abilities humans use to perform job tasks. An online tool allows users to easily navigate the full set of scales and levels at aicapabilityindicators.oecd.org. AI moves fast. The current ratings include AI systems released up to the end of 2024, meaning “reasoning models” such as GPTo3 and DeepSeek’s R1 will be rated in the next edition.

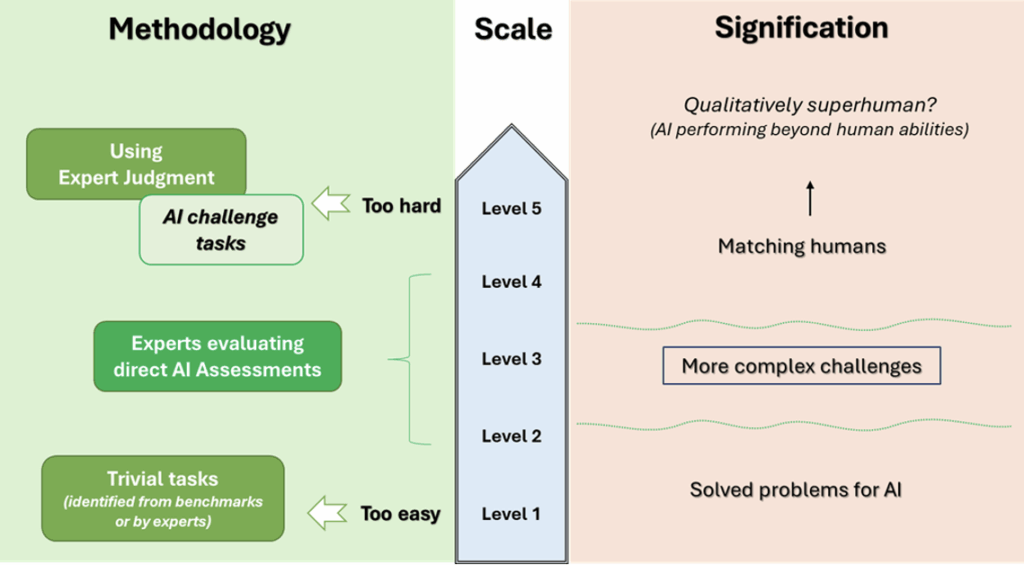

The scales are based on the types of technical benchmarks described earlier. Our team worked with an expert group of 30 AI researchers, psychologists, labour economists and assessment specialists to link the results of these benchmarks to human abilities. A structured peer review by 25 researchers followed the development process.

The scales aim to convey the major developments in each capability from the past towards a hypothetical future in which AI can replicate all human abilities. Those already achieved are at the lower levels, while those remaining are at the upper levels.

Across the scales, we see the strengths and weaknesses of different categories of AI models. For instance, while LLMs achieve the highest rating on the Language scale (level 3) thanks to their ability to produce human-like language and vast knowledge, they do not top the ratings across the board. Neuro-symbolic models such as Google’s AlphaZero are the most performant systems on the Creativity scale (level 3) due to their ability to generate solutions that are not only useful but also surprising to humans. In contrast, symbolic AI systems (level 2), nostalgically referred to as good old-fashioned AI, still outperform LLMs (level 1) on the Problem-solving scale due to the latter’s issues with hallucinations and brittleness.

Overall, AI is still well behind humans across all scales.

Nevertheless, many human jobs only require the abilities at the lower end of these scales. Jobs requiring tasks at levels 2 and 3 are most likely to be impacted by AI soon. For instance, AI is currently at Level 3 on the Knowledge, Learning and Memory scale, which includes generative tasks like creating illustrations or summarising information. This means jobs that include such tasks are likely to be impacted by AI. On the other hand, jobs that require capabilities at Level 4, such as operating in unknown environments, are unlikely to be affected by current AI systems.

The report includes beta indicators and an invitation for feedback from two key stakeholder groups: AI researchers and policymakers. The AI evaluation work of researchers provides evidence for the indicators, while the ability to interpret and leverage insights is vital for informed policy. We also welcome feedback from other stakeholder groups. The OECD will release the first comprehensive version of the indicators after receiving feedback from stakeholders and developing a systematic update protocol.

The future of the Indicators

So, are we claiming to be the only ones who know what AI can and cannot do? In a formal context, sort of.

We hope that the framework and indicators presented here are merely the beginning. The beta indicators’ ratings are already informative and can be utilised in pilot studies examining the implications of AI across diverse policy domains. If our methodology can be scaled up, we believe this framework can serve as the foundation for developing new assessments of AI that test its capabilities to replicate relevant human abilities.

Nevertheless, they need to be updated to reflect the capabilities of AI systems in 2025, and our framework requires refinement, including the integration of additional benchmarks. We will update the scales in early 2026 and are actively seeking partners to help strengthen the indicators and apply them to analyses of how AI impacts education and the labour market.